An Introduction to Value Investing - confronting value traps

Fundamentals 01: This post covers the issues to consider when value investing. It is an update to include notes on how to analyze companies and other value investing tips. Note that there is a PowerPoint presentation of this article on SlideShare under "Baby steps in value investing". Revision date: 23 Jul 2023

|

| "Investment is simple but not easy" Benjamin Graham |

You want to invest in listed companies from a value investing perspective but do not have the time or knowledge to analyze and value the companies. Then join me as I share my analysis and valuation of such companies. I hope to shortcut your learning journey.

I am a value investor, and the video explains why I chose this investing path.

As a value investor, you would invest when the price is at a significant discount to the intrinsic value. The question then is whether your assessment of intrinsic value is accurate.

- If your valuation is wrong, then the stock is cheap for a reason, and you have a value trap.

- But if your assessment of intrinsic value is correct, then you have a bargain.

From the above perspective, value traps and bargains are two sides of the value investing coin.

More importantly, value investing is about confronting the value trap question. Value traps are fundamental to value investing.

Following this perspective, you have to develop 3 skills if you want to be a successful value investor:

- How to analyze companies that I will discuss here.

- How to value companies that will be covered in Fundamentals 02.

- How to mitigate risk which will be covered in Fundamentals 03.

Contents

- How I got started

- What to consider at the start?

- What to buy?

- How much to buy - position sizing

- When to buy or sell?

- Valuation - the means to confront value traps

- Company analysis - the building blocks for assessing value traps

- Pulling it all together

|

How I got started

I first started investing in companies listed on Bursa in the early nineties. Yep! I did not start early.

I had no sound basis for selecting the companies to invest in then. Needless to say, I only earned about what I would have earned if I had kept my monies in fixed deposits. Luckily, I only had a very small amount invested then!

About 15 years ago I decided to look at investing in equities seriously i.e. as a way to generate better returns. So, I started to learn as much as possible about how to invest by crawling the web.

There is a lot of information on the web on how to invest and value companies. In hindsight some of them are nonsensical. Unfortunately for a beginner, it is hard to tell which is the appropriate approach.

It took me several years to finally weed out the “rules of thumb posing as theory” from those that had some theoretical foundations. And this was only after spending time learning from several investment and valuation textbooks.

It took me even longer to conclude that value traps are fundamental to value investing. You are looking for bargains and the challenge is to find the real bargains. The false ones are value traps.

With this insight, I began to categorize bargains into

- Those based on growth - the Compounders.

- Those based on assets - the Net Nets.

- Those based on quality - the Quality Value.

- Those based on distributing profits - the Dividend yielders.

|

What to consider at the start?

Before we dive into the process of value investing, there are a few questions about investing that all beginners ask:

- Why invest?

- Why invest in the stock market?

- Why value investing?

- Is value investing a thing of the past?

- If value investing is so good, why doesn’t everyone do it?

- What are the most important skills to become a value investor?

- As a value investor, which would be the best sources to learn accounting?

- What drives the stock price?

- Is it gambling?

- Can you use value investing principles for day trading?

- How much should I invest in stocks?

- Can I make money?

- How does a value stock give returns to an investor? How long is the duration?

- Are there any situations where panic is the correct response in the stock market?

- Do I know of anybody who has lost everything in the stock market?

Why invest?

The main goal of investing is to protect your savings from the ravages of inflation. You also grow your wealth in the process.

- To achieve the former, you need an investment approach that provides a return that is above the inflation rate.

- To achieve the latter, you need to harness the power of compounding. But compounding requires consistent returns over decades of investing.

From the inflation perspective, the only reason you don’t invest is that you do not expect inflation in your country.

One of the reasons cited by many for not investing is the fear of losing money. Many forget that by not investing, you will also lose money through inflation.

Of course, to hedge against inflation, your return has to be greater than the inflation rate. If you are not able to achieve this, the value of your money will also decline. So, there is a minimum return that you need from your investment.

If you get a return that is greater than the inflation rate, you will grow your wealth. If you are aiming to generate some positive return, then shouldn’t you try to achieve as high a return as possible?

I have found that value investing enables me to generate consistent returns that are above the inflation rates.

At the same time, I have been a “serious” value investor for only 15 years. I need another decade or two to compound my net worth.

Why invest in the stock market?

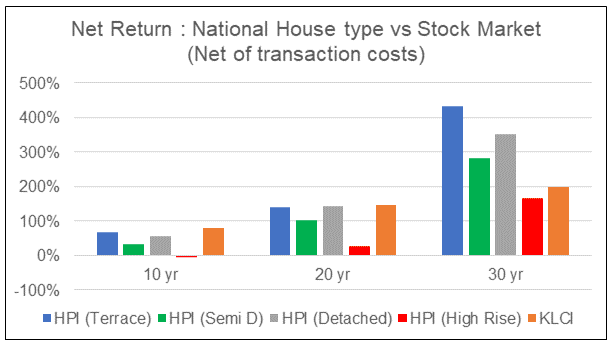

The main reason why you would choose stocks over other assets is that it generally delivers the best return over a long holding period.

- “…they provide the highest potential returns. And over the long term, no other type of investments tends to perform better.” Morningstar

- “.. the possibility to increase the value of the principal amount invested. This comes in the form of capital gains and dividends.” BlackRock

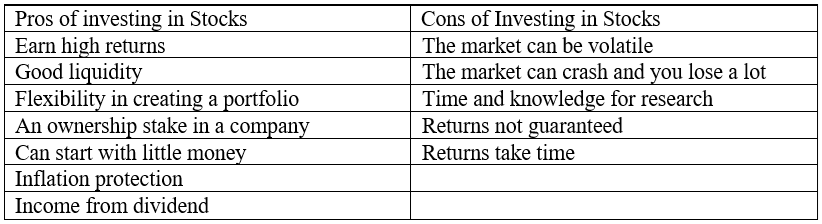

There are also other advantages and disadvantages as summarized in the table.

|

| Table 1: Pros and Cons of Investing in the Stock Market |

Why value investing?

There are 3 critical issues in investing:

- What to buy – the valuation thesis.

- How much to buy – positing sizing and portfolio construction.

- When to buy or sell.

Value investing provides a good way to answer these three questions:

- You buy when price < intrinsic value.

- You buy more for those with the highest conviction.

- You sell when price > intrinsic value.

This is not to say that other investing styles are not able to provide the answers.

There are many investing styles eg technical, quants, factor, and indexing. Each one of them will have their proponents and their way of answering these questions.

Investing is a zero-sum game. There are two sides to every transaction and when you buy a stock thinking that it will go up, there is another party on the other side thinking the opposite.

The question is who is right?

I would like to think that since with value investing, I am buying a bargain, I am on the right side of the trade.

Is value investing a thing of the past?

Value investing is about buying companies at a discount to their intrinsic value. So why would this be a thing of the past? What has changed is what you incorporate into the intrinsic value estimate.

Value investing is an investment concept:

- You can determine the intrinsic value of a company.

- Invest when the market price is trading at a significant discount to the intrinsic value.

- Have in place a series of risk mitigation strategies to protect yourself.

So, if you take the above perspective, then value investing is a timeless concept.

The question of whether it still works has to be seen in the context of a portfolio, time horizon, and your skill in analyzing and valuing companies. If you have 20 to 30 stocks selected based on value investing principles and you have 3 to 5 years investing horizon, value investing still works.

When you invest, there are 3 critical questions mentioned earlier. Value investing gives you the answers to them. As such, why would you think that value investing is a thing of the past?

However, the fund management industry has a different perspective of what is value investing. They classify stocks as value or growth stocks depending on some PE or PB valuation metrics.

Indirectly they then deem buying “value stocks” as value investing. I think this is a wrong interpretation of the concept.

There is no such thing as a value stock. Value stock and growth stock is a fund management industry shorthand for stocks with low PE or PB. You should be more interested in whether a stock is trading below its intrinsic value.

If you follow the fund industry idea of value investing, you can see that it is not dead either.

If value investing is so good, why doesn’t everyone do it?

Value investing is the concept of buying stocks at a discount to their intrinsic value. Whether you will make money with this approach depends on you.

To be a good value investor, you need to be able to buy when the market is down and everyone is in a panic.

It may take a long time for the market to recognize the value and re-rate the stocks. Do you have the patience to wait for this? Depending on the stocks and market, this may take several years.

Then when the market is bullish and everyone is buying, you should see this as a time to get out - make your money and wait for the downturn.

It is a behavioral challenge as you are going against the crowd. Not everyone can behave in this manner. That is why although value investing is simple, it is not for everyone. No glamour. You look like an idiot most of the time.

Secondly just because you bought at a discount to the intrinsic value, it does not mean that your estimate of the intrinsic value is correct. If you got it wrong, then you are not going to make any money.

What are the most important skills to become a value investor?

Value investing is about business analysis and valuation.

In learning to be a value investor, focus on these two disciplines. They probably have different concepts and require different skills.

I started by reading books on value investing. The problem with most books is that they are mostly about concepts. I did not come across any “how-to” book that covered the A-Z of value investing.

Investing is a skill that you develop over time. You need an iterative approach of getting a bit of knowledge and then practicing it.

The best way is via practice. Skills don't come from reading books alone. It is about practice as well.

Investing is like driving - there are some basic principles but when you look back there are not that many of these. It is all about practice.

But there is a trick to this. You should learn and practice in incremental steps ie learn a bit, do some paper investments, review your mistakes, and then go and learn a bit more.

After all, you have to develop 3 skills:

- How to analyze companies.

- How to value them.

- How to mitigate against risks.

Company analysis is about trying to understand its prospects - track record, business direction, competitive strategy, and management capabilities so that you have realistic assumptions for the valuation.

To value companies, you need a valuation methodology. Invariably you will need to make assumptions about the business prospects. So you need to ensure that the valuation is not some mindless number-crunching exercise.

And when you are ready to invest, you need a risk mitigation process to protect yourself against bad luck and your behavioral biases.

My advice to those starting on the value investing path is that you need to develop the skills to do all the 3 well.

As a value investor, which would be the best sources to learn Accounting?

You don't need to learn Accounting. Of course, you need to be able to read and understand the financial statements, but you don't need to be an accountant to do this.

As a value investor, you need to be able to do 2 things well.

- How to analyze companies so that the inputs into the valuation are realistic.

- How to value them.

These are very different from accounting.

Having said that, a bit of accounting knowledge is useful for the following reasons:

- In analyzing and valuing companies, you rely on their financial statements. The quality of the earnings, and whether there are any financial shenanigan affects the reliability of your fundamental analysis.

- There are differences between how accountants treat certain items and how an investor would view them. A good example is the treatment of R&D. Most accountants would expense them off to the P&L. However, in many instances, these should be capitalized and depreciated. The treatment affects the returns.

What drives the stock price?

Technically supply and demand determine the stock price whether in the short term or long term.

But the supply and demand for a stock are derived items. I used the term “derived” because they are dependent on the outlook for the stock

The outlook is a function of sentiment and the company’s fundamentals. In the short run, sentiment rules but in the long-run fundamental rules.

The challenge is that sentiments are also influenced by fundamentals.

You will realize that two main investing styles have developed because of this:

- The technical one that tries to capture the sentiments by looking at price and volume signals.

- The fundamental one that tries to relate the price to the business performance.

Generally, the former tends to be short-term focussed whereas the latter is better for long-term investing.

Is it gambling?

Gambling is an activity that depends purely on luck. Buying a lottery is a gamble. So, playing the one-arm bandit or roulette in a casino is gambling.

But there are some activities that while appearing to be a gamble require some degree of skill. I am sure that the professional poker player will say that poker is such a game.

When it comes to the stock market, some invest blindly hoping to get rich by luck. But you need skills to be a successful value investor. Of course, a bit of luck helps.

When you have an activity where skill is required to win when played regularly, I would not consider it gambling. Investing in the stock market is one such activity. Just because there are those that blindly invest hoping to win by luck does not make the game a gamble.

Using the gambling analogy, if you are a skillful investor you are acting as the house in a casino where the odds are stacked in your favour. If you don’t develop your skills and invest as a novice you are likely to be like the guest in the casino.

Can you use value investing principles for day trading?

Day trading is based on price action ie you trade based on your reading on how the price is going to move. Price is sentiment-driven and the day trader is reading market sentiments.

Your success as a day trader may be due to your ability to read crowd behavior. I am sure it is not due to an understanding of businesses.

Value investing is based on buying when the price is significantly below the intrinsic value and selling when it is the opposite. Your success depends on your understanding of the business.

I am not sure why the day trader would want to use value investment concepts since intrinsic value does not change daily and does not depend on market sentiments.

The point is that there are several investing styles eg technical vs fundamental, factor investing, indexing, etc. Each has its investment concepts and behavioral requirements. A buying signal under one style may not be a buying signal for another style. Given this, you should not mix the concepts.

How much should I invest in stocks?

You should consider your investment in stocks as part of your asset allocation or investment plan.

If you know how the future will turn out, you will be an idiot not to invest all in the asset class with the best return.

The reality is that we don’t know which asset will deliver the best return. So, we spread our net worth among many assets. If one asset class does badly, hopefully, the others will do well enough to offset the bad performance.

What you set aside for stock investing should be seen as part of your asset allocation plan.

Asset allocation is a wide subject and is covered in another post.

Can I make money?

You invest to protect your saving against inflation and hopefully grow wealth.

Can you be successful?

If you look at all the successful investors, they tend to focus on one particular investment path

- Warren Buffet made his fortune from value investing.

- Cliff Asness of AQR Capital is a well know quant.

- Thomas Price Jr is known as the father of growth investing.

- Jesse Livermore is a well-known trader.

If you want to be successful, you have to be an expert in your chosen path. You must acquire the appropriate knowledge and learn how to apply it through case studies and paper transactions. Once you have mastered it, you can then invest with real money.

You may worry that with so many professional or institutional investors, you will have a hard time making money.

As a retail value investor, you have certain advantages over the institutional or professional investor.

- You can have a contrarian view without having to worry about losing your job.

- You can have a long-term investing horizon.

- With a smaller amount to invest, you have choices not available to the larger funds.

I would think that if you master the investing skill you have a good chance of making money.

You make money if you know what you are doing.

How does a value stock give returns to an investor? How long is the duration?

If you are a value investor, you look for opportunities when the stock price is trading at a significant discount (eg 30%) to the intrinsic value. You hold onto the stocks until the market re-rates.

I am a long-term value investor in that I analyze and value companies to buy and hold long-term. I then sell when the market price is > 20 % of the intrinsic value. So, I make the difference between undervaluation and overvaluation.

I have been investing as a value investor for the past 15 years with a portfolio of 35 stocks. My average portfolio turnover is 10 % to 15 % annually - indirectly holding stocks for 7 to 10 years.

Once in a blue moon, I am lucky to find a stock that becomes overvalued within a year. But I have even sold off stocks after 10 years without seeing any major price change only to see the stock price double months after I hold them.

The point is that you don’t control the holding period as you cannot predict market behavior. You can only control the discount and over-valuation.

I have gone through 2 cycles where the portfolio value had declined by > 40%. First in 2008/09 due to the US subprime crisis and recently in Mac 2020 due to Covid-19.

Notwithstanding the long holding period and the drawdowns, my portfolio CAGR over the past 15 years is 1.3 times the stock market index return. Not all my stocks made money but the ones that do more than offset the ones that don't.

I make money by selling the overvalued stocks and then reinvesting in other undervalued stocks ie I do not hold the stocks forever.

I guess that if I was good enough to identify stocks that would always be the best stock, then I would be holding onto stocks forever. But I always worry about the Kodak and Nokia of the world.

I am not good enough to identify “forever” good stocks so my approach is to have cycles of selling overvalued stocks and then reinvesting in other undervalued stocks.

The other point about being a long-term investor is that your total gain is from capital gain + dividends. I estimated that about 1/3 of my total return has been from dividends.

Are there any situations where panic is the correct response in the stock market?

As a value investor, you should ignore price volatility. But what happens when you see a large price drop within a short period? Do you panic and sell?

You would panic if you don’t know what you are doing. There are 5 ways to invest:

- Buy and sell pieces of paper. This is a market sentiments-driven approach where you chase the popular stocks.

- Buy and sell part ownership of businesses. You look for opportunities where the price is less than the value of the underlying business as determined by its fundamentals. You believe that price will eventually reflect the business value.

- Factor investing. Here you buy stocks based on certain characteristics eg momentum, value, etc that have been proven to explain the price performance of stocks.

- Indexing. If you don't have the skills to invest based on the above approaches, you should index.

- Invest blindly. Here you rely on tips, and luck to make money.

If you invest following the first or last approaches panic should be an appropriate response.

But if you are a skilled trader, skilled value investor, skilled indexer, or even a skilled factor investor, you would have your risk mitigation plans. They would provide downside protection so that you don’t have to panic.

Do I know of anybody who has lost everything in the stock market?

I am very sure that if you talk to a group of people who have engaged with the stock market, you will find that everyone would have lost some money at some point in time.

The likelihood is that half of the group would probably have got richer at the expense of the other half.

But human nature is such that if you ask the group whether they have lost money, and you ask in public, you will find that almost everyone will say they made money.

Do I know of anyone who has lost everything in the stock market?

The likelihood is that you won’t find retail investors among this group as I don’t think any retail investor would have bet all their savings in the stock market.

But do I know of owners of listed companies who have lost everything in the stock market? Yes, because owners tend to have all their net worth invested in the company they founded.

In the Asian economic crisis, many Malaysian owners lost everything. This is partly because they borrow money using their shares as collateral. When the market fell, they started to buy more shares to support the share price so that the banks would ask for more collateral. This worked in “normal times”.

But in a widespread economic crisis, the market fell longer than the owners could have the cash to support the share prices. The result is that many lost everything when the banks forced-sold the shares (when the borrowers could not come up with more collateral).

The moral of the story - the people who lost everything are the owners who borrowed. Those who did not have any debt survived and got over the crisis. So, don’t borrow to invest.

Retail investors lost some money but I have not heard of any retail investor losing all. So, asset allocation is important even if you don’t borrow to invest.

What to buy?

I follow 2 key principles in deciding what to buy.

- Buying at a discount to the intrinsic value. This serves both as risk mitigation as well as provides the upside.

- How to protect against a permanent loss of capital i.e. risk management.

Ya. In layman's terms - buy a bargain and don't lose money.

I am sure that when you start to analyze a company, there will be tons of information many of which are nice to know, but not critical in investing. To narrow down the analysis and valuation, I classify my investments into the following:

1) Compounders – these are high returns and growth companies where I hope to benefit from the growth in intrinsic value.

Generally, they will be trading at greater than book value and any Earnings Value (EV) model would not capture their full value. In such instances, I look at returns as the valuation metric.

2) Quality value – these are companies with above-average Q Rating where the market has not recognized their real worth causing them to trade at discounts to their intrinsic values.

I would only buy if the market price is at least at a 25 % discount to the EV.

3) Turnarounds – these are companies facing some temporary issues. However, the market has priced them as if there is no hope of any recovery.

The main challenge here is valuation as any historical EV may not capture the value after the turnaround.

4) Net Net – these are companies trading at a discount to their Graham Net Net value. They may or may not be facing turnaround issues. Like the Turnarounds, the challenge here is to ensure that they are not value traps.

5) Dividend Yielders – these are companies that are purchased mainly for their dividends. Examples are the REITs.

The above classification serves the following purposes:

- All valuation involves assumptions about the future. One way to handle the uncertainty is to have a margin of safety. The various types of investments have different degrees of uncertainty. I am more confident about the intrinsic values of Net Nets than the intrinsic values of Compounders. I thus have different margins of safety for the various type of investments.

- Having various categories of investments is one way to diversify the portfolio.

- It helps to focus on the type of valuation method to use. Compounders and quality-value companies are better valued with earnings-based methods. The value of Net Nets is based on asset values.

You will realize from the above that my decision on what is a good stock to buy is then dependent on the reasons why price < intrinsic value.

- It does not matter whether it is a penny stock or whether it is the highest-priced stock.

- It may require contrarian thinking as many of the stocks I choose are not the popular ones.

How much to buy - position sizing

So you have identified what to buy. The next issue then is how much of it to buy - what is referred to as positioning sizing.

There is a relationship between the 3 key parameters in a portfolio.

- The total amount to be invested in the portfolio.

- The number of stocks in the portfolio.

- The amount to be allocated to each stock ie the position size.

These 3 parameters are linked. Given the total to be invested, the amount you allocate to each stock affects the number of stocks in the portfolio.

For example, if you have RM 100,000 to invest and you decide to allocate RM 25,000 to each stock, you will end up with 4 stocks in your portfolio.

Position sizing and portfolio construction are part of risk mitigation. Every stock has both risks specific to the company as well as general market risks. You can mitigate against specific company risks by holding a diversified portfolio of stocks.

The theory suggests that you can reduce most of the risks associated with individual stocks by holding about 20 to 30 companies. What remains then is the general market risk which cannot be diversified away. You will have to consider other measures to protect against market risk.

Given the total amount to be invested and the target of about 30 companies for a diversified portfolio, you can now determine the amount to be allocated to each stock.

In terms of portfolio construction, I am a bottom-up stock picker. My portfolio is made up of companies from the 5 categories of stock as per above that were independently purchased.

In other words, I do not pre-determine the number of companies from each category or sector for the portfolio.

Having said this, I limit the exposure to any one sector to 30 % of the total portfolio value. We cannot be too careful.

When I first started, I allocated about the same sum to each of the companies in my portfolio. Then I came across the Kelly formula.

You cannot apply the formula literally as the formula relies on repeatable probabilities. But you can use the principle that the optimum investment is one where you invest the most in the company with the best probability of success.

It simply means that you should allocate larger sums to those for which you have the most conviction.

In practice, this meant that you allocate larger sums to companies meeting a combination of the following metrics:

- Highest dividend yield.

- Higher Q Rating.

- Higher margin of safety.

Given the total investment sum and a target of 30 companies in the portfolio, you then come up with the amount to be invested in each company.

When to buy or sell?

So you have identified what to buy and how much of the stock to invest in.

When do you execute the trade?

You will find that in many cases, I generally take some time to build up to the invested sum

- I have found that when I have committed money to an investment, I become more focused on assessing the company. This is probably a behavioral issue but because of this, I have learned to build up my position over a 3 to 6 months period.

- Secondly, to ensure that I get the lowest price, I do use some technical indicators to provide some insight into whether the price has the potential to go lower. I look at candlestick patterns and trendlines.

- To clarify, these technical indicators are used to “time” my entry and exit after I have decided to buy or sell based on value investing principles. I do not use technical signals to decide on whether to buy or sell.

- Like the entries, I seldom exit a stock in one go but rather spread it over several batches. This is to get a balance between selling too early and regretting not selling when the price collapse after running up.

Although I am a long-term investor, it does not mean that I never sell my shares. I have sold under the following conditions:

- When the market price is > 20 % of the computed intrinsic value. However, in a range-bound market, this criterion is modified to sell when the market price = computed intrinsic value. You guessed it - I want to realize my gain.

- When the investment thesis is no longer valid either due to changes in the market and/or errors in my assumptions. This is a cut-loss strategy. Have some money to fight another day.

- I also sell if, after 7 years of investing in the stock, the market persists in mispricing. The logic is to allocate the monies for another prospective stock. The reality is that you can lose patience after some time so this cut-off period will depend on your personality.

To put the selling strategy in perspective, over the past 15 years about less than 5 % of my portfolio has been sold because of an invalid investment thesis or long waiting period.

The majority have been sold because they have reached the targeted return. My target is to achieve a 15% compounded annual total return. I compute my total returns as:

Total return = (capital gain plus total dividends received) divided by the original investment.

My track records are:

- About 5 % of the stocks achieved the target within the first year of the initial purchase.

- About 5% are duds.

- The majority takes about 3 to 5 years to reach the targeted return.

- About 1/3 of the total returns come from dividends.

- Overall, I achieve a total return that is about 2 to 3 % higher than the total return of the stock market index.

The Holding Period

There are 2 ways to grow wealth:

- Invest in a portfolio that you never sell because they are the companies that can increase shareholders' value over many decades. Unfortunately, I cannot identify such companies.

- The other way is to start with a portfolio of undervalued stocks. When some of the stocks become overvalued, you sell them and then reinvest all the monies into other undervalued stocks. You then repeat the cycle for a different set of portfolio stocks.

To be able to execute this portfolio plan, you need:

- To be able to find replacement stocks every year. Thus, having several types of investment helps this strategy.

- You need an investment process that delivers consistent returns that is independent of the type of companies in the portfolio. I find that value investing enables me to achieve this.

- You need patience. It is a plodding way to grow wealth. Effectively you are the tortoise in the race rather than the hare.

The above explains why I am a long-term investor.

- It is because business fundamentals do not change overnight. It may even take years for companies to turn around.

- It may even take longer for the market to recognize changes in business prospects.

But there is another angle for being a long-term investor. If you want to benefit from the power of compounding, you have to invest continuously for decades.

In summary, then, there are 2 ways to make money from your stock investment:

- Invest in the “forever” best stocks. These are stocks that will continue to be the best in terms of growth and value creation for shareholders. If you find such stocks there is no need to sell them as their value and prices will continue to go up.

- Invest in undervalued stocks and when they become overvalued you sell them and reinvest the money into other undervalued stocks.

Given the Kodak and Nokia of the world, I am not sure whether there are “forever” best stocks. Even Warren Buffett who professed to hold onto stocks forever also sells some of his stocks. Have you checked to see if the stocks you hold are still the best today?

I can’t identify the “forever” stocks so I follow the latter approach. It works as long as you reinvest the money from the sale into other undervalued stocks. Conceptually your investment fund increases in size each time you sell and reinvest. That is how you grow your investment fund.

Valuation - the means to confront value traps

Whether is stock is a value trap or a bargain is assessed by comparing the price with the intrinsic value.

The key then is determining the intrinsic value.

There 3 general ways to value a company:

- Asset-based where you view the assets as a store of value.

- Earnings-based where you view the assets as a generator of value.

- Relative value where you value the asset by comparing it to the price of a similar asset.

I do not consider relative valuation an intrinsic valuation approach and so I use the following two approaches:

- Asset-based valuation.

- Earnings-based valuation.

OK, it is going to get a bit technical here. But I am just giving an overview and you can refer to the Definitions posting if you want to go deeper.

Asset-based value(AV)

Asset-based valuation focuses on the value of the company’s assets.

There is a relationship between the assets of a company and the returns that can be generated from the assets.

According to economic theory

- High returns relative to the cost of funds will attract competitors and this will eventually drive returns down.

- If returns are low relative to the cost of funds, some companies will exit the industry and this will lead to better returns.

The result is that in the long run, the returns would equal the cost of funds.

In the context of valuation, I see the following:

- If there are persistently low returns, it must mean that the assets are overvalued. Expect some impairment so that the asset value will be commensurate with the returns.

- If the returns persistently above the cost of funds, the company must have some economic moat to maintain this position. In such situations, the intrinsic value of the company would be higher than the asset value ie the asset value serves as a floor value.

There are several perspectives under this approach from the Graham Net Net, NTA, Book Value to Reproduction Value.

How have I used the Asset-based valuation?

- Occasionally I have found companies whose prices are below their Graham Net-Nets. Many consider Net Net as a proxy for the liquidation value. If these are operating companies, I would consider them as ones with a very high margin of safety and always ended up investing in them.

- In times of economic distress, many companies are trading below their NTA and Book Values. This is a sign to focus my analysis of such companies.

- The assets and liabilities of financial institutions are generally marked to market. They already captured prevailing market values. Thus any financial institutions with market prices below their NTAs deserve closer investigation.

- And of course, the Asset-based value is used with the Earnings-based value as part of my assessment of the company’s performance.

Earnings-based value (EV)

Here you view the assets as a generator of value. The intrinsic value is the discounted value of the cash flow generated by the business over its life.

The challenges here are then:

- Forecasting the cash flow.

- Determining the discount rate.

- Determining the life of the business.

In the Earnings-based method, the value of the company is determined by both the Residual Earnings method and the Free Cash Flow method. Yes, you probably have to read the Definitions.

But no need to get too hung up on the definitions. I will do the calculations and take care of the reconciliations, etc.

In practice, I have found that are differences in the computed values from both methods. This is probably because the information for the valuation is extracted from different parts of the financial statements.

So I take the average of the values computed by the two methods as the final Intrinsic Value.

Furthermore, I generally undertake the above valuation under 2 scenarios:

- Assuming no growth i.e the Earnings Power Value (EPV).

- With growth.

As the above method is just valuing the operating assets i.e. it ignores excess cash, investments, and associates. and other non-operating assets, the value of these non-operating assets has to be added in order to arrive at the total value of the company.

Triangulating the intrinsic value

All valuations are based on assumptions about the future.

Since we don’t have a crystal ball, to handle the uncertainty involved in the valuation:

- I use both the Asset-based value and the Earnings-based value together with other valuation metrics to triangulate the intrinsic value.

- Having triangulated that intrinsic value as says $ X. I then factor in a margin of safety eg 30% so that the intrinsic value in the analysis is now $ 0.7 X.

- I buy when the price < $ 0.7 X.

In addition to determining the intrinsic value, I also use several other metrics that are used by other more experienced value investors. These include:

- The Acquirer’s multiple.

- The Greenblatt Magic Formula.

|

| Chart 1: Performance Index |

Company analysis - the building blocks for assessing value traps

Valuation is an important element to determine whether its stock is a value trap or a bargain. But it needs to be backed by a good understanding of the company's business. This is the company analysis aspect of the investment process.

This is to ensure that the valuation exercise does not turn into a number-crunching one that does not reflect reality.

That is why I consider company analysis as the building block for assessing value traps.

I have being involved at the senior management level in running companies. There is not much difference in analyzing the business in the context of running it compared to analyzing it as part of the investment process.

However, the focus is different. Here you are trying to formulate your investment thesis and you want your outlook on the business and its valuation assumptions to be realistic.

Accordingly, I frame my analysis to answer the following:

- How did it get here?

- How does it make money?

- Where is it heading?

Items such as products, corporate structure, management style, and shareholders are background information.

Apart from looking at the business per se, I also spend considerable effort to understand:

- Management performance.

- The key business risks.

We know the importance of management in driving the business. The challenge is how to evaluate them as you are not able to meet with them as a minority shareholder.

I try to present an objective picture of management by looking at the following:

- Are they owner-managers?

- How long have they been with the company?

- How have they performed relative to their peers?

- How have they allocated capital?

When it comes to risk, my analyses and valuation are based on a long-term view of the business. I try to identify and assess those factors that will affect the long-term prospects of the business. You can consider these as strategic risks.

My view is that as a minority shareholder, you are not management. Hence you leave all the operational and other short-term risks to management to resolve. You thus try to look at those risks that will change the nature of the business.

Take analysts' reports with a grain of salt

When you start to look at companies, one of the sources of information will be the analysts' reports.

Over the years, I have read many research houses' reports on Bursa-listed companies. Analysts are warned. I am going to say things unpleasant about your profession.

I do not find many reports to be very informative as what is presented in the report can be picked up from the company’s announcements.

Secondly, many Malaysian analysts seemed to focus on what companies are going to do over the next one to two quarters. They all say that they have a long-term view of the business. But a significant part of the report is dedicated to what happened in the last quarter and the issues faced currently.

Furthermore, many analysts provide a target price for the company featured. I must admit I do not understand the logic of the target price. Most analysts (except those providing technical analysis) claim to be looking at fundamentals.

Setting a target price seems more like forecasting what the market will do. There is a disconnect as the analyst report is on the company’s fundamentals. Yet the analyst somehow jumped from such fundamental analysis to forecast the market price.

There is then the question of valuation. Most analysts use market multiple methods to value the company featured. Very few determine what I consider the intrinsic value of the company.

|

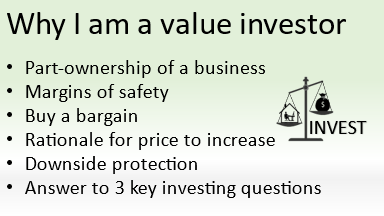

| Chart 2: Why I am a value investor |

Pulling it all together

There are many investment styles, from one based on fundamentals as summarized above to those based on technical charts. Some trade frequently compared to those that invest in the long term.

All value investors have their own beliefs that drive their answers to the value trap question – what many refer to as the Investment Thesis. You build the Investment Thesis based on business analysis, valuation, and risk mitigation.

I invest as a value investor because it puts you on the right side of the transaction. It provides a way to answer the 3 basic investing questions:

- What to buy?

- How much to buy?

- When to buy and sell?

Leaving aside the above investing questions, there are more fundamental reasons why I am a value investor. These can be categorized into 5:

- Part-ownership of companies. I have a strong business background. As such I understand how business operates. In value investing, you focus on the business fundamentals. My background gives me a good advantage.

- Margin of safety. The key to value investing is determining the value of a company. All valuations are based on assumptions. The margin of safety concept recognizes this “imprecise” task. I am an engineer and use margin of safety because we all know that there is always uncertainty even in engineering calculations. As such this margin of safety concept appeals to me.

- Buying a bargain. We all love bargains. I fail to see why we should not use the same bargain idea when buying companies. It is great to follow an investing style that is aligned with how I buy things.

- Rationale for why the price would increase. To make money from stocks, you need the stock prices to increase. By buying stocks whose prices are lower than the fundamental values, there is an economic reason why the price of the stock you buy would go up.

- Downside protection. I am a conservative investor. Value investing with its margin of safety and buying bargains provide downside protection.

END

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

How to be an Authoritative Source, Share This Post

|

Disclaimer & Disclosure

I am not an investment adviser, security analyst, or stockbroker. The contents are meant for educational purposes and should not be taken as any recommendation to purchase or dispose of shares in the featured companies. Investments or strategies mentioned on this website may not be suitable for you and you should have your own independent decision regarding them.

The opinions expressed here are based on information I consider reliable but I do not warrant its completeness or accuracy and should not be relied on as such.

I may have equity interests in some of the companies featured.

This blog is reader-supported. When you buy through links in the post, the blog will earn a small commission. The payment comes from the retailer and not from you.

Ekonomisk kris, I have read all the comments and suggestions posted by the visitors for this article are very fine,We will wait for your next article so only.Thanks!

ReplyDeleteExcellent article. Very interesting to read. I really love to read such a nice article. Thanks! keep rocking. regulatory compliance

ReplyDeleteSome truly wonderful work on behalf of the owner of this internet site , perfectly great articles . Expense management system

ReplyDeleteThis is truly a great read for me. I have bookmarked it and I am looking forward to reading new articles. Keep up the good work!. Early retire calculator

ReplyDeleteThis content is written very well. Your use of formatting when making your points makes your observations very clear and easy to understand. Thank you. corporate expense management

ReplyDelete