The Basics Of Valuation - Picking out Value Traps

This is the heart of value investing – to buy an equity stake in a company at a price that is at a discount to its value. The question then boils down to how to determine what the company is worth.

At the same time. you have to be wary of value traps. How do you tell what is cheap for a reason (a value trap) vs what is undervalued (a bargain)? Valuation is the key to picking out value traps.

There is no one answer to what a company is worth. You have to triangulate from several angles. Yet you want to keep it simple so that you do not lose the forest from the trees.

Big picture. Simple yet insightful. Come from several perspectives.

To do all of these you need a framework. I have one that came from many trials and tribulations.

I am assuming that you have the skills and interest to analyze and value companies. If you don't have the interest or skills yet want to invest based on fundamentals, you can still do so by relying on experienced analysts. Those who do this well include people like Seeking Alpha.* Click the link for some free stock advice. If you subscribe to their services, you can access their business analysis, valuation, and risk assessment.

|

Contents

- What to consider at the start?

- How I approach valuation

- Strategic insights

- Analyzing Asset Value

- Analyzing Earnings Value

- Handling special cases

- What do I assume in my valuation?

- Pulling it all together

What to consider at the start?

- What is value?

- Why value companies?

- What are the main valuation methods?

- How to learn valuation?

- How to pick out value traps?

What is value?

Why value companies?

- If the company wants to raise funds by issuing additional shares, then knowledge about the value of the company is important.

- A company undertaking a share buyback programme should also be interested in the value of the company. Management should not be buying back overvalued shares.

- Valuation is also important for companies undertaking a merger or acquisition exercise.

- Knowing whether the value of a company has increase may also be an important component of senior management compensation.

Methods of valuation

- Relative valuation

- Asset-based valuation

- Earnings-based valuation

How to learn valuation?

- Understand the concepts and method

- Practice, practice, practice

- Some of the pitfalls I experienced so that you can avoid them.

- The steps in my approach so that as you can have a better understanding of the valuation covered in the various case studies

Picking out Value traps

- Errors in the valuation. This could be due to having the wrong assumptions, misunderstanding the concepts, or even computation error.

- Unforeseen circumstances that eventually lead to a deterioration in the business fundamentals. There is then a corresponding decline in the intrinsic value

How I approach valuation

- Asset-based valuation (AV)

- Earnings-based valuation (EV)

Strategic insights

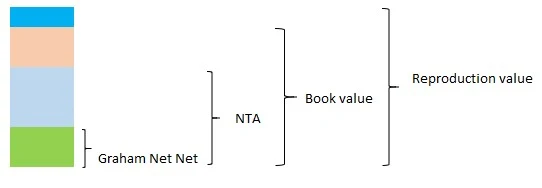

Analyzing Asset Values

- There are instances where the value of properties has been captured at historical costs. In such instances, if the value of the properties is significant, I do make an adjustment to reflect the current market price.

- Do not be surprised if occasionally you come across negative Graham Net-Net. In such cases, I treat this as zero.

- The most challenging to determine is the Reproduction Value. You are trying to estimate what it takes to re-create the company with all its customers' relationships, product branding, and any R&D that have been charged out. For some sectors, you may actually have to reduce the value of its Plant, Property, and Equipment as it is now possible to build a new plant cheaper due to technological progress.

- For property-based companies with significant landbank, many analysts estimate what is known as the RNAV – the Revised or Re-valued Net Asset Value. The most reliable way to estimate the RNAV is to base the property value on a professional valuer’s assessment.

What can go wrong?

Analyzing Earnings Value

What are some of the challenges I have found in using the Earnings-based valuation method?

- Growth does not add value unless the company's return is greater than its cost of capital. If you work out the numbers for such a case, you will find that the value with growth would be less than the value without growth. In such cases, I ignore the value with growth.

- Some companies retain a significant amount of cash. I have occasionally come across cases where the market price is around the value of cash and other non-operating assets. Yes, these are prized findings.

- If there are significant differences between the value from the Residual Income method compared to that from the Free Cash Flow method, I choose the Residual Income. You will meet such situations if the company has an expansion programme. It will then require significant capital expenditure that will affect the value using the Free Cash Flow method.

- If you are valuing a conglomerate operating in several different sectors, the risks and hence the cost of capital will be different for the various sectors. In such cases, you have to do more work to first value the various sectors independently. Then add them all up to get the value of the conglomerate – the sum of the parts valuation.

What can go wrong?

Information for Earnings-based valuations is picked up mainly from the Income Statement.

Handling special cases

When textbooks teach you about valuation, the focus is on specific concepts. Examples used to illustrate the concept tend to show idealized situations.

Rea-life is a bit messy. Items do not necessarily fall into place like the textbook examples.

That is why understanding the principles is important so that you can make the appropriate interpretations.

I list below the common real-life problems that I have encountered over the 1,000 valuations I have done.

Valuing companies with a large cash balance

- If the cash has been invested in marketable securities, I would consider the market value of the securities.

- I have seen arguments that the value of the cash should be less than the face value of the cash if the company has a poor track record of investing its cash.

- If cash is deposited with the bank and earns interest, should you value it taking into consideration the interest earned?

Valuing companies with intangible assets

- Those that are captured in the Balance Sheet

- Those that are not recognized in the Balance Sheet

- Goodwill resulting from some M&A exercises

- Expenditure for certain services whose usefulness extends over several years. A good example is computer software.

Valuing Companies with negative earnings or cash flows

- Companies at the start-up stage

- Companies undergoing some turnaround

- If the problems are due to some structural problems ie long term problems, you should not consider investing in such companies.

- If the problems are temporary, the challenge for Earnings-based valuation is projecting the turnaround performance

- Looking at the historical profits can provide one clue.

- Another way is to benchmark against industry performance if the problem is not industry-wide

- The most challenging approach is one where you have to make assumptions about various parameters eg sales, margins

- For such cases, if I am lucky and the Graham Net Net provides the margin of safety, I do not rely on the Earnings-based values.

- Alternatively, I look at the Asset-based value and build in a few more years of losses and/or impairment. If there is a margin of safety after doing this, I invest

Valuing companies with negative working capital

Valuing cyclical companies

- Use the actual average values over the cycle

- Use the company average margins over the cycle and then apply this to the most recent revenue to derive the normalized earnings. The same principle applies to capital expenditure and working capital

Valuing companies with project-based revenue

- The key feature is there are many customers each one buying a product or two. Company revenue is from the aggregation of the many individual small sales

- Unless the products or services are out-dated, they will continue to generate revenue every year.

- The revenue for such companies is from the projects being executed. It is obvious that their performance will depend on their order books.

- Some projects are completed within the financial year while some are stretched over several financial years.

- The key characteristic is that one project or contract accounts for a significant part of the annual revenue

Valuing companies in distress

Valuing holding companies or conglomerates

- The pure holding companies. These companies do not have operational control of their investments

- Those with operational control

- Consolidated value. This is looking at the holding company as a group and valuing it based on the consolidated earnings/cash flow

- Sum of parts value. If the information for different segments is available, you could value individual segments. This is especially relevant if the segments have different risks. The value of the holding company is then the sum of the various segment values

- One way is then to use the Dividend discount model to value such companies. The Dividend discount model weakness is that unless all earnings are paid out, dividends do not represent owners-earnings.

- The other way is to use the Asset-based value. The Asset-based method is likely to be higher than the value derived from the Dividend discount model. It is common to then factor in a discount for lack of control and/or liquidity.

- I do not think that the discount is intrinsic. Imagine what happens when the holding company disposes of all the investments and then distribute all the cash. If the discount is “intrinsic” it would mean that the shareholders would not get all the cash from the sale.

- If the net asset value has already accounted for the holding company’s costs this would be double-counting

Valuing options

- “warrants” or “sweeteners” to encourage support for the corporate proposals. Such warrants are options.

- Convertible loan stocks. In the company’s accounts, part of these are treated as loans and part of this are treated as options

What do I assume in my valuation?

- The most reliable method with minimal assumptions when determining the AV

- To the EPV with assumptions about the sustainable earnings but without any assumption about growth

- To the least reliable Value with Growth where you have to make assumptions about the growth prospects.

- Companies operating “steadily”. These are situations where I can assume that historical performance provides a good sign of the future.

- “Companies in transition”. These can be companies facing some secular decline. This could be due to the demand for its products, or/and those undergoing structural changes. It could also be those at the start-up stage. Looking at the historical performance here is not very helpful.

- Revenue growth AND EBIT growth AND TCE growth > 8 %. The 8 % is the average

- Correlation for Revenue growth, EBIT growth, and TCE growth > 0.7 i.e. they explain 49 % of the variation

- Capital expenditure – I first estimate the capital expenditure as a % of revenue for each year. I then use this together with changes in the fixed assets to estimate the capital expenditure

- Working capital – I first estimate the net change in working capital as a % of revenue for each year. I then use this together with changes in working capital extracted from the Cashflow statement to estimate the net working capital requirement

- Depreciation – this comprises all depreciation and amortization

Pulling it all together

END

|

The article you've shared here is fantastic because it provides some excellent information that will be incredibly beneficial to me. Thank you for sharing Residential Property Valuation Dubai. Keep up the good work.

ReplyDelete