Can we learn anything from investment case studies?

Case Notes 01: This post has been updated to cover what you need to learn in the context of value investing and the role of case studies. Note that there is a PowerPoint presentation of this article under "Learn how to invest using investment case studies". Revision date: 10 Dec 2023

In the world of finance, investment case studies serve as valuable narratives. They offer a retrospective lens into the successes and pitfalls of various investment decisions.

By looking at real-world scenarios, we can get insights on the various factors that affect investment decisions.

These case studies provide a nuanced education for those learning investing. They shed light on the intricacies of the ever-evolving financial landscape.

This article delves into the question of whether we can learn anything from investment case studies. Join me as I explore:

- The advantages and challenges of learning from case studies.

- The steps involved.

- What to look out for when learning from case studies

|

Contents

- What investment students need to know

- Valuing a business

- Thinking about prices

- Value traps

- What can you pick up from my Case Studies?

- Business Analysis

- Valuation

- Risk

- Benefits

- Disadvantages and limitations

- How to learn from Case Studies

- Learning steps

- What to look out for

- Where to find investment case studies

- My experience

- Takeaways

What investment students need to know

Warren Buffett in his 1996 letter to his shareholders said:

“To invest successfully, you need not understand beta, efficient markets, modern portfolio theory, option pricing, or emerging markets. You may, in fact, be better off knowing nothing of these. That, of course, is not the prevailing view at most business schools, whose finance curriculum tends to be dominated by such subjects. In our view, though, investment students need only two well-taught courses – How to Value a Business, and How to Think About Market Prices.”

The Warren Buffett quote above sums up what I will focus on in my blog

- How to value a business.

- How to think about market prices.

Valuing a business

While valuation is a numerical-based exercise, you have to ensure that it does not turn out to be number crunching. Use assumptions and projections grounded in reality.

One way to ensure this is to first have a good understanding of the business you are valuing - the company analysis.

However, there are several perspectives when analyzing companies:

- Management would be looking at ways to improve its operations and/or business direction

- Creditors would be assessing the risk of extending loans and/or credit to the company

- Investors would be determining whether to invest

As a minority investor, you have to remember that you are not management. Unless you are an activist investor, you are not likely to decide on how the company operates.

Your company analysis is thus from the perspective of trying to determine where the business is heading. Consider the challenges and risks so that you can make some realistic assumptions in your valuation.

What you focus on in the analysis will be different from that of management and other parties.

Thinking about prices

“Long ago, Ben Graham taught me that ‘Price is what you pay; value is what you get.’ Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.” Warren Buffett

If you are a stock trader, price and volume data are critical information because the focus is on trading pieces of paper. The fundamentals and/or intrinsic values of the companies are not important

But, if you are a value investor, market prices are also important. You are buying and selling based on how the market price compares to the intrinsic values

Both price and value are the two sides of the same coin. Understanding the difference between price and value is the core principle of value investing.

- While you can get the price of a stock (for listed companies), there are no quoted intrinsic values. In practice, you have to estimate the intrinsic values yourself.

- Different investors will have different estimates of the intrinsic value of a company. Contrast this with the stock price. While the stock price may fluctuate, at any one point, there is one price representing the thinking of the crowd at that time.

- Relative value is not intrinsic value. Relative value is assessing the worth of a company by comparing it with its peers. Intrinsic value is based on the company’s fundamentals and is related to the discounted cash flow generated by the business over its life. So, the market price represents the perceived value by the crowd and is not the intrinsic value.

- Market price changes often whereas intrinsic value does not change on a day-to-day basis.

Technically market prices are set by supply and demand. According to economic theory

- If there are more buyers than sellers then the price will adjust upwards until we have the situation where the number of buyers = number of sellers

- If there are more sellers than buyers, the price will adjust downwards until we have an equal number of sellers and buyers

Of course, this is an economic model that works in a freely competitive environment and may not reflect what is happening in the stock market.

I prefer to look at the reasons why people buy or sell. For every transaction, there are people from opposite sides:

- The buyers are those that expect the price to give up so that they can make money

- The sellers are those who that think they will lose money or that they have made enough as they don’t expect the price to go up in the future.

So the real question is what drives the expectation.

I believe that it is a combination of sentiments and business fundamentals. In the short run, sentiments rule while in the long run, business fundamentals have more influence. The challenge is that sentiments are also influenced by fundamentals

These 2 views of what drives stock prices have given rise to 2 investing methods

- The technical school uses price and volume information as a proxy for market sentiments. These people trade pieces of paper.

- The fundamental schools have value investors as one good example. These consider investing as being a part-shareholder of a company and as such view the business fundamentals as the main driver of value.

Value traps

By its nature, value investing is about

- Identifying undervalued companies,

- Investing in them and

- Selling them when they are overvalued.

The critical components are then

- Determining the intrinsic value and

- Comparing the prevailing market price with intrinsic value.

That is where value traps come in.

Value traps are companies that while appearing to be cheap, are not cheap as there are some fundamental issues with the company. So, if you invest in such a company you will be caught in a value trap as the price will continue to be low.

When you compare price with intrinsic value, there are several possible scenarios

- The intrinsic value is correctly assessed and with the price below the intrinsic value, the stock is a bargain

- The intrinsic value is wrongly assessed. Although the price is below the assessed intrinsic value, the true situation will eventually come to light. When this happens, the price will continue to languish. You have a value trap

You can see that value traps and bargains are the opposite sides of the value investing coin.

Value traps are part and parcel of value investment.

The only way you can avoid a value trap is to assess the intrinsic value correctly.

The various case studies are attempts to drive home this point.

|

What can you pick up from my Case Studies?

Warren Buffett has referred to his “two courses” several times since the letter. I don’t know whether it is an urban legend but he supposedly mentioned that he would do one case study after another when asked about the “How to value a business” course.

The case study method of learning is the hallmark of the Harvard Business School. The idea is that by using real-life situations, you can gain insights that may be difficult to teach via lectures.

You learn better from examples.

Each of my company case studies focuses on 3 issues

- What is the business of the company and where is it heading?

- What is the intrinsic value of the business?

- What are the key risks?

While valuation and risk mitigation are separate subjects covered elsewhere in the blog, they are an integral part of any valuing investment process.

Business analysis

The starting point for any business analysis is to run through the historical Annual Reports.

I then supplement this with industry insights

- Competitors Annual Reports are also good sources of such information

- I also look at industry research

You will notice from my case studies that I don’t provide details of the Financial Statements. But I do rely quite a lot on them to gain information about the current and future financial health of the company.

The financials are important building blocks but are not the end in themselves. Think of them as the bricks and cement in a building. You are interested in the building and not the bricks and cement.

It is not the numbers that are important. It is what is behind the numbers that are more important.

To do this, I read

- The Financial Statements and the accompanying notes,

- The Chairman’s Statements and the Management Discussions and Analysis.

What about Corporate Governance, Risk Management, and Sustainability Statement? I skimped through them if they were motherhood statements. I only pay close attention if they can inform me of the long-term prospects of the company eg impact on the business direction, and key risks.

The quantitative analysis is a straightforward part.

It is always the qualitative analysis that is the most challenging. You are trying to get a picture of

- Where the industry is heading,

- The prospects of the company, and

- Whether management would be able to meet the challenges over the next 10 to 20 years.

I don’t think you can get this with quantitative analysis alone.

I hope that the various case studies in my blog have shown that company analysis and valuation are not about being an EXCEL-king.

I did not start with a spreadsheet and you will notice that the focus is on understanding the business ie

- How does the company make money?

- Where is it now?

- How did it get here?

- Where is it heading?

- Where does it want to go?

We all have our approach in trying to get the answers to these questions. I prefer what I have done in my case studies and will be using this framework in all my case studies.

I also did not use the conventional SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) technique in my analysis. I think this is overused and I have seen many SWOT analyses that are not linked to what to do next.

But the main reason I tend to avoid SWOT is that you are analyzing the company to see where it is heading. You are forecasting the future from an investor’s perspective. You are not management.

Unless you are an activist investor, you don’t have much hope of changing the way the business is run or heading. Yours is the minority shareholders’ perspective.

I believe that I have provided a framework to enable you to identify the issues in such a way as to help in the valuation process.

The point is that there are many techniques available from Porter’s 5 Forces, Factors analysis to the BCG matrix. Each will have its uses and weaknesses.

It is not the technique that is important. It is the answers that you want and I will be using a variety of analytical techniques in all my case studies.

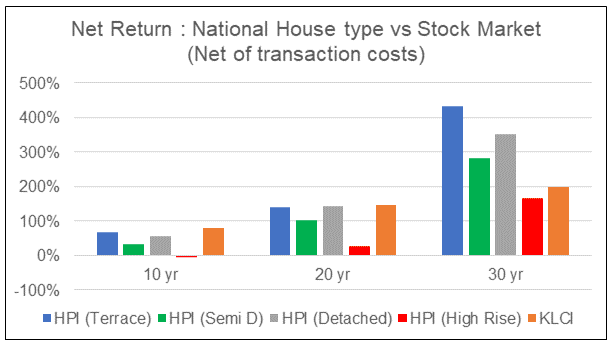

Valuation

I use 2 main valuation methods to derive the intrinsic value

- Asset-based where I consider the assets as a store of value. I rely on the Balance Sheet for this.

- Earnings-based where the assets are seen as a generator of value. The intrinsic value is the discounted free cash flow generated over the life of the business. I rely on the Profit and Loss and Cash Flow statements for the information required for this.

I also have a host of other valuation techniques to help me triangulate the intrinsic values. These include the Acquirer’s multiple and the Greenblatt “Magic Formula”.

I extracted all the information for these above valuations from the company’s financial statements.

While I do not show the financial information specifically in my case studies, I have

- A spreadsheet with at least the past 12 years' financials for each company.

- A financial model that extracts the relevant statistics for my financial analysis and valuation.

The chart below provides a snapshot of such an analysis.

Risk

I view risk as a permanent loss of capital and my risk management approach is to

- Identify all the possible causes for any permanent loss of capital

- Assess the threats in terms of the impact and the likelihood of them occurring

- Adopt a host of risk mitigation measures

You can see that you need to have a strong understanding of the business to assess the risks.

In other words, the company analysis serves two purposes

- Ensure that your assumptions about the prospects of the company used in the financial model are realistic

- Enable you to identify the threats and hence take the appropriate risk mitigation measures

Of course, some of the threats are related to the investment process and my behavior while others are related to the business itself.

To handle the latter, I cover the key risks in my company analysis as shown in my case studies.

Benefits

There are several benefits when you learn from investment case studies. They can be summarized as follows.

Real-world application. Investment case studies offer practical, real-world examples. They bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and its application. This approach enhances understanding and facilitates better decision-making.

Risk management insights. Case studies often highlight the importance of effective risk management. They show how risks were identified, assessed, and addressed in specific scenarios. These can help you can develop a more robust risk management framework.

Strategic decision-making. You can gain insights into the factors that drive successful investment decisions. These will help refine your analytical and decision-making processes.

Market dynamics. Case studies help you understand how various factors such as economic conditions and geopolitical events impact investments. This is crucial for making informed decisions.

Enhanced analytical skills. Case studies require you to assess various factors such as financial statements and industry trends. This will sharpen your analytical skills

Confidence building. With the lessons from case studies, you are better equipped to face challenges in the actual market.

In summary, learning from investment case studies provides a multifaceted educational experience. They can contribute to the development of a more informed and adaptive approach to investing.

Disadvantages and limitations

There are also potential disadvantages and limitations to consider when learning from case studies.

Hindsight bias. Case studies are often analyzed with the benefit of hindsight. These can create a distorted perspective. In real-time decision-making, you do not have the luxury of knowing future outcomes. Relying too heavily on hindsight can lead to overconfidence.

Unique context. Each investment case is unique. The specific context may not be easily transferable to other situations.

Incomplete information. Case studies may not provide a complete picture of the information available at the time of the investment decision. In reality, you must make decisions with imperfect and incomplete information, which adds an extra layer of complexity.

Market dynamics. Financial markets are dynamic, and conditions can change rapidly. Case studies may become outdated or irrelevant as market dynamics evolve. This may make it challenging to apply historical lessons to current situations.

Biases in selection. The choice of which case studies to study may introduce biases. Selecting only successful cases may create an overly optimistic view of investment strategies. Exclusively examining failures may instill unnecessary fear and caution.

Neglect of macro factors. Case studies often concentrate on micro-level factors specific to individual investments. Neglecting broader macroeconomic factors could impact investment outcomes.

Lack of emotional context. Case studies may not capture the emotional and psychological aspects of decision-making.

Oversimplification. To make case studies more digestible, the author may simplify some complexities. This can lead to a false sense of understanding of the challenges.

To mitigate these disadvantages, you should approach case studies with a critical mindset. Consider the limitations of each study, and use them as part of a broader educational framework. Case studies should complement, not replace, a well-rounded understanding of financial markets

However, I believe that these disadvantages would be mitigated if you cover a lot of different case studies.

How to learn from Case Studies

My investment case study is a description of a company’s business, its prospects, risks, and my estimate of the intrinsic value.

It recounts events or problems in a way that so that you can learn from their complexities and ambiguities.

There are two ways for you to learn from the case study

- Passively by merely looking at how I have analyzed and valued the company. You can use this as a template for your analysis and valuation

- Actively by trying to analyze and value the company yourself before reading the case study. Then compare your analysis and valuation with mine.

If there was a formal classroom setting, there would be an opportunity to discuss the analysis and valuation with the class. You would have the chance to reflect on how your analysis and valuation might change as a result of the class discussion.

Unfortunately, without a classroom setting, the next best alternative is to do the comparison yourself.

It is obvious that for the case study to be useful, you must have the necessary knowledge first. The case study will then help you to understand what you have learned. More importantly, it will help to develop your skills in

- Qualitative and quantitative analysis

- Dealing with ambiguities

It should be remembered that to develop the necessary investment skills you need both knowledge and practice. Case studies provide one way to see what you have learned being applied in a real-world setting.

The alternative to case studies is a simulation or paper transactions. But these are stories for another post.

Learning steps

Here are key steps to derive meaningful lessons from investment case studies:

Identify key factors. Pinpoint the critical factors that influenced the investment outcome. This includes market conditions, economic indicators, and company-specific information.

Understand risk management. Analyze how risk was assessed and managed in the case study.

Evaluate decision-making. Examine the rationale behind the investment choices. This include analysing financial statements, market trends, and competitive landscapes.

Learn from mistakes. Where appropriate understand the mistakes made in the case study. Assess the consequences of errors and explore alternative strategies.

Consider diversification. Examine the role of diversification in the case study. Understand how a diversified portfolio or lack thereof influences the overall risk and return profile.

Stay informed. Apply lessons from case studies to current situations. You should adapt strategies based on changing economic landscapes.

Simulate scenarios. Apply the lessons learned by simulating similar scenarios in a controlled environment. Utilize investment simulations or paper trading to practice implementing strategies.

Dissecting and reflecting on investment case studies through the above lenses. If you do so, you can extract valuable lessons and develop a more nuanced and informed approach.

What to look out for

There are many types of case studies and different author cover different things. I would suggest that when you come across an author for the first time, use the following checklist.

Contextual relevance. Ensure that the case study is relevant to your situation. Context matters. Applying lessons from a contextually inappropriate case may lead to misguided decisions.

Quality of information. Evaluate the quality and reliability of the data and information presented. Rely on well-researched and documented cases. This will ensure that the insights derived are based on accurate and credible information.

Consider different perspectives. Investment decisions are often subjective, and case studies may present a particular perspective. Be open to considering different viewpoints and interpretations of the same case.

Identify biases. Recognize potential biases in the case study. They could stem from the author’s perspective, the source of the information, or the outcome.

Complexity and simplicity. Assess the complexity of the case study. Some cases may be overly intricate, making it challenging to extract clear lessons. Others may oversimplify complex market dynamics. Seek a balance that aligns with your level of expertise and understanding.

Distinguish between correlation and causation. Understand the difference between correlation and causation. Just because two events occurred together does not imply a cause-and-effect relationship.

Consider market conditions. Take into account the prevailing market conditions during the period covered by the case study. Economic, industry and geopolitical factors play a significant role in investment outcomes. As such understanding their influence is crucial.

Relevance to your strategy. Identify actionable insights that align with your investment strategy. Not all lessons from a case study may be directly applicable to your approach.

Update information. Changes in the economic landscape since the case study’s occurrence might impact the relevance of the lessons learned.

Where to find investment case studies

There are other sources of investment case studies than just my blog. The table below provides some guidelines. Some sources may offer free access, while others may require a subscription or purchase.

Remember to critically evaluate the quality and relevance of the case studies you choose. Consider such factors as:

- The source’s credibility.

- The context of the case.

- The applicability to your learning objectives.

|

Sources |

Links to

some examples |

|

Online

platforms

|

|

|

Investment

blogs |

|

|

Financial

news outlets |

· The Wall Street Journal · Financial Times

|

|

Books |

· 26 Value Investing Case Studies (2011-2017)

|

|

Academic

Journals

|

· Harvard Business Review · Journal of Finance

|

|

Professional

institutes |

· CISI

|

My experience

I do not consider myself a newbie. Yet I spend considerable time looking at case studies written by others. I group why I do so under the following.

Sanity check

All analyses are based on assumptions about the future. I look at how others have analysed the companies to see whether I have missed things. I like to compare investment thesis as a check against bias. You would be surprised how often I have come across investment thesis that is completely different from mine. Such thesis would recommend a buy when I think it is a hold or sell.

Valuation

Even though different analysts share similar views on the business prospects, they may differ in the way the companies are valued. They could use different valuation approaches. Some rely on relative valuation while I prefer DCF. Even with DCF, there are different models and discount rates. Looking at different valuations gives me a sense of the range of possible values. Think of it as some form of margin of safety.

Building blocks

There are many occasions where I build on the analyses provided by others. Rather than repeat what has been covered elsewhere, I cover a different timeframe or do a complementary analysis.

Investment decision

Sometimes, I just adopt the analyses provided in lieu of my own. I often do this when I am looking at markets that I am not familiar with. It is much faster to gain insights this way than carrying out a detailed fundamental analysis yourself

Takeaways

- I hope my case studies have provided you with a framework to analyze and value companies. They are meant to cover the 2 areas suggested by Warren Buffett – how to value companies and how to think about market prices.

- My case studies are meant for both newbies and experts. For the experts, I hope they provide alternative perspectives. For the newbies, I hope that you use them in an active manner.

- For the newbies, treat the case studies as complementary sources of learning. You would still need to gain the theoretical knowledge through the traditional sources.

- For the newbies, I have provided learning steps and what to look for when learning from case studies.

- If you are new to investing, I suggest that you read the 3 Fundamentals posts and then follow me on all the Case Studies and Case Notes. I think it would be a good idea once you have gone through 3 or 4 case studies to re-read the Fundamentals. I am sure you will pick up more points in the second round of reading.

- The key insight is that value traps and bargains are the opposite sides of the value investing coin. One of the goals of the case studies is to learn how to distinguish which side of the coin a particular company is on.

My case studies assumed that you have a business background and quantitative skills to analyze and value companies. If you do not have the skills to do so, and you still want to be a value investor, one way is to rely on other experts like Seeking Alpha.* to assess and value companies for you. Click the link for some free stock advice. I suggest that you give them a try.

END

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

How to be an Authoritative Source, Share This Post

|

Disclaimer & Disclosure

I am not an investment adviser, security analyst, or stockbroker. The contents are meant for educational purposes and should not be taken as any recommendation to purchase or dispose of shares in the featured companies. Investments or strategies mentioned on this website may not be suitable for you and you should have your own independent decision regarding them.

The opinions expressed here are based on information I consider reliable but I do not warrant its completeness or accuracy and should not be relied on as such.

I may have equity interests in some of the companies featured.

This blog is reader-supported. When you buy through links in the post, the blog will earn a small commission. The payment comes from the retailer and not from you.

nice post

ReplyDelete