How to mitigate permanent loss of capital in an awesome way.

Fundamentals 27. This is an update of my approach to mitigating risk from a permanent loss of capital perspective. It pulls together the threads from my various risk articles. If you have gone to them, you would be re-directed here.

There are 2 schools of thought about investing risk:

- The volatility school that views variance as risk.

- The permanent loss of capital schools that view risk as a permanent reduction of the amount invested.

The volatility school has strong academic credentials. This branch of finance theory has developed to a stage where you can numerically bring risk into the valuation process.

However, all the discussions on permanent loss of capital as risks are qualitative. How can you manage risk if you are following the permanent loss of capital school? Specifically:

- How to methodically bring the permanent loss of capital into the investment process?

- How to compare risks between two companies?

I have a 3-minute video that provides an overview of all the above.

This article shows how to translate the permanent loss of capital concept into a practical way to mitigate investment risk.

But I hasten to say that the 2 views of risk are not mutually exclusive. Even as a value investor, there are benefits from bringing volatility into your overall risk mitigation process.

Contents

- Risk management

- Tapping into my experience

- What is risk?

- Permanent loss of capital

- Possible causes for permanent loss of capital

- Assessing the threats

- Risk mitigation

- Case study

- Volatility

- Modern Portfolio Theory

- Capital Asset Pricing Model

- An integrated risk management framework

- Identifying the root causes

- Threat matrix and risk mitigation measures

- Behavioral dimension

- Pulling it all together

|

Risk is not some number. It is about some events that can lead to a permanent loss of capital. If you take this view, then risk mitigation should involve every stage of your investment process.

- Start with an overview of risk and an asset allocation plan.

- Dovetail this into your stock portfolio.

- Adopt the corporate risk management process to assess risk and bring it into your investment process.

For details of the first component, refer to the following articles:

For details of the second component, refer to the following articles:

This article focuses on the last component. I covered 2 aspects:

- A framework for assessing permanent loss of capital.

- Bringing volatility into my risk mitigation framework.

Risk management

“Risk management is the identification, evaluation, and prioritization of risks followed by coordinated and economical application of resources to minimize, monitor, and control the probability or impact of unfortunate events or to maximize the realization of opportunities.” Wikipedia

There is a long association between risk management and insurance. But in the 1950s other forms of alternatives to insurance started to appear. This was when the cost of insurance was considered high relative to the benefits.

The discipline evolved and it became a more widespread concept with the growth of corporate governance.

Today there is even an ISO 31000 standard for risk management. This provided the principles and guidelines for effective risk management.

The risk management process involves the following:

- Identify the causes that can lead to the risk.

- Assess the risk in the context of the impact and the likelihood of the occurrence.

- Formulate the mitigation measure to manage the risk.

The strategies to manage them cover:

- Avoidance - what can be done to prevent it from happening.

- Reduction - how to minimize the impact of any risks.

- Transfer - is there a way to transfer the risk and/or the consequences to another party.

- Accept - in some instances where the cost of mitigation outweighs the benefit of the mitigation strategies, it may be better to live with the risk.

If you consider the permanent loss of capital as a risk, there is no reason why we cannot use the risk management framework to manage risk.

|

Tapping into my experience

There is a lack of literature on how to assess permanent loss of capital. I thus had to develop my risk management process.

I was fortunate as I had served as a member of the Audit Committee in several listed companies since the 90s. Over this period, the focus of the Audit Committee had shifted from internal audit to corporate governance. And corporate governance began to focus on risk management.

I tapped into my corporate risk management experience to develop my risk management framework.

The other fortunate thing was my engineering background. In my early work life, I worked in factories looking after quality management among other things.

That gave me the opportunity to be familiar with quality control tools. The one that I remembered best was using the Ishikawa or fishbone diagram to trace defects.

Whenever there is a defect, you first list down all the possible causes. At this stage, this is merely guesswork. There could be several causes for a defect. Some are direct, and some are indirect. Some are second-level effects.

I used the Ishikawa diagram to help frame the cause and effect so that you can identify the root causes. You then formulate measures to eliminate the root causes.

Two things can happen. If you are lucky, you don’t see the defects any more.

Most of the time, the defects still occur. When this happens, the conclusion must be that the activity that you tackled was not the cause. You then move on to another suspected cause.

You then update the Ishikawa diagram.

To cut a long story short, I used the tools from the factory and Audit Committee experience to develop my risk management framework.

Actually, it was not only a trial-and-error process but also a rambling and iterative one. What you see today is a framework that has gone through several rounds of improvement.

What is risk?

In investing there are 2 schools of thought when it comes to risk.

- Those that view it as volatility.

- Those that view it as a permanent loss of capital.

The former has lots of academic credentials. The theory has developed to a stage where risk can be modeled mathematically. Furthermore, risks are separated into systemic and non-systemic risks. You can diversify the non-systemic risks. You live with the systemic risks by demanding higher returns for the higher risks you take.

Unfortunately for us value investors, there is very little academic research into the permanent loss of capital.

Some would consider risk as the likelihood of not earning what you expect. I don’t think making less is not the same as losing some of the capital.

Over the years, I have suffered such permanent loss of capital from 3 situations:

- Selling during a temporary price drop thereby converting the temporary loss into a permanent loss. I no longer have this risk having learned to invest for the long term. At the same time, I do not invest using borrowings so that there is no pressure to sell an investment at the wrong time.

- A deterioration in the intrinsic value to permanently below the purchase price. Over the past 15 years, I have had 3 cases of such losses. Two were due to outright fraud by the companies while the other was due to business risks.

- Privatization by the controlling shareholders. There have been occasions where I have benefited from a privatization exercise. However, there were a few privatization exercises where the offered price was below my purchase price. OK, you can argue that I should have bought the shares with more margin of safety.

The moral of the story? You have to differentiate between the effect (losing some of your capital) and the reasons (cause of the loss) if you are going to manage risks.

There is another difference between volatility and permanent loss of capital. With the latter any loss is permanent. It cannot be reversed. The best you can do is cut loss or look at other ways to make back the loss. That is why learning how to invest and taking preventive measures are critical.

Permanent loss of capital

There is no question that all the proponents of the permanent loss of capital agree that it represents the risk in investing.

· “... permanent loss of capital is the risk that you might lose some or all of your original investment if the price falls and you sell for less than you paid to buy.” Weitz Investments Management

· “True investment risk is a permanent impairment of capital. In other words, an asset depreciates and never recovers.” Forbes

· “A better way to think of risk is as the possibility or probability of an asset experiencing a permanent loss of value or below-expectation performance.” Investopedia

Yet, I have not come across studies that attempt to quantify the potential “permanent loss of capital” in an investment.

Rather most proponents generally focus on why volatility is not risk. They then proceed to describe how permanent loss of capital can occur.

This is unlike the volatility school which separate risks into systematic and non-systematic ones.

- You manage non-systematic risk through diversification.

- You aim for higher returns for taking on greater systematic risk.

- You can also bring risk to your valuation by incorporating Beta into the cost of capital formula.

However, the permanent loss of capital school approaches risks qualitatively. It then focuses on mitigating this permanent loss of capital.

Nothing illustrates this way of thinking better than the risk portion in the book “The Art of Value Investing”.

This is a book by John Heins and Whitney Tilson. It collects the thoughts of experts on various valuing investing topics, including risk.

Not surprisingly, there is no attempt to quantify or assess this permanent loss of capital. Instead, the experts offer insights on the measures taken to mitigate a permanent loss of capital.

The following quote from the book exemplifies the position.

“Guarding against risk is built into every aspect of the best value investors' strategies, from the ideas they pursue, their buy and sell disciplines, how they build positions, how they structure their portfolios, how they manage cash, and how they hedge.”

Unfortunately, if you are learning to invest, this will not help you assess and mitigate risks. This article is an attempt to fill this void.

Possible causes for permanent loss of capital

Identifying all the causes of investment risks is critical. So, when I first started to think about risk, I spent a lot of time researching investment risk literature. I wanted to produce a universal list of investment risks.

It is very sad to say that there is a lot of muddled thinking out there.

For example, I have come across an article that described 4 ways to mitigate risks. It then went on to cover diversifying into different sectors, countries, market capitalization, and styles. To me, it was only one measure i.e. diversification.

Many people also confuse between cause and effect. Some of the recommended risk strategies don’t address the root causes.

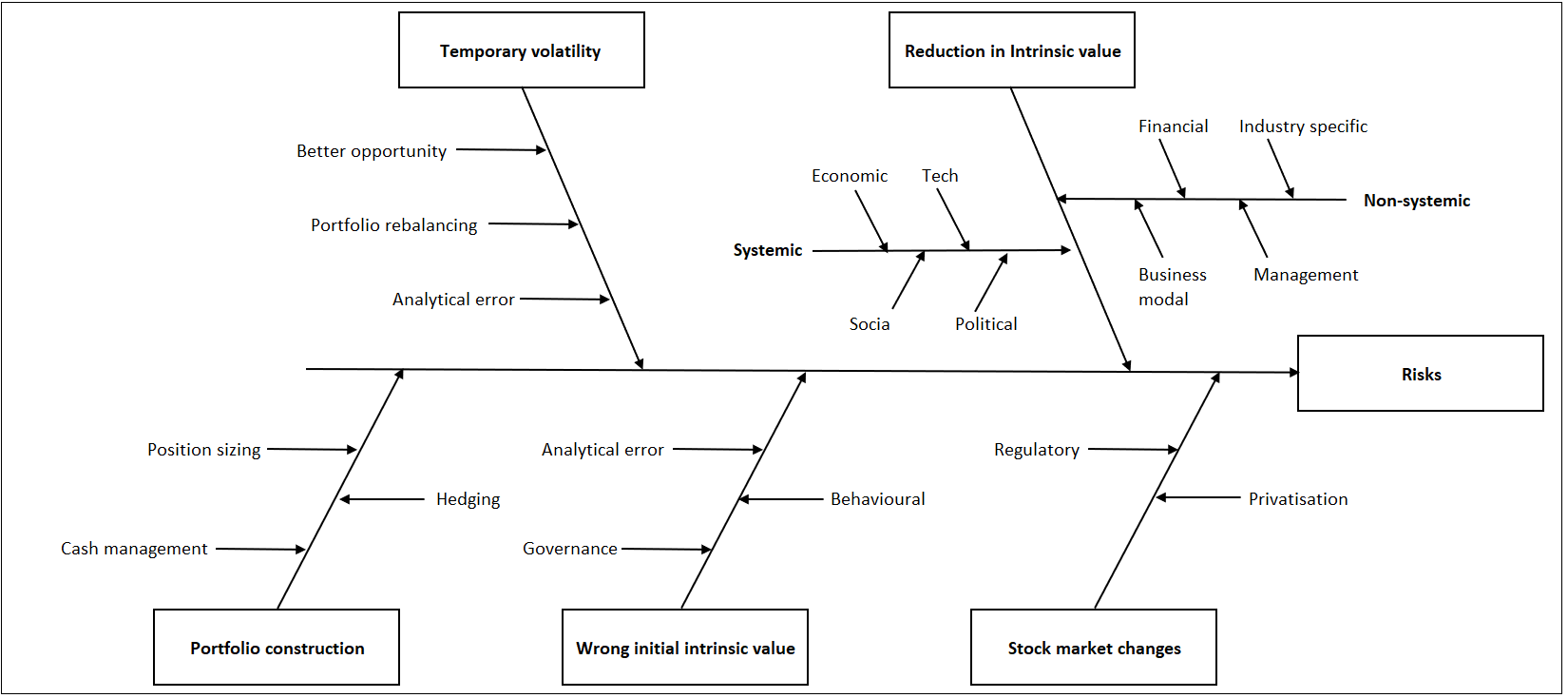

This is where the Ishikawa or fishbone diagram came in.

Ishikawa diagram

An Ishikawa diagram shows the causes of an outcome and is often used in manufacturing to show where quality control issues might arise.

It is sometimes referred to as a fishbone diagram. It resembles a fish skeleton, with the "ribs" representing the causes and the final outcome appearing at the head of the skeleton. In such a diagram:

- The head of the fish is created by listing the problem and drawing a box around it.

- A horizontal arrow is then drawn across the page with an arrow pointing to the head. This acts as the backbone of the fish.

- The key causes are identified that might contribute to the problem. These causes are then drawn to branch off from the backbone with arrows, making the first bones of the fish.

- For each key cause, the root causes of the problem are identified. These contributing factors are written down to branch off their corresponding key cause.

- The chart below shows the structure of an Ishikawa diagram.

Ways to suffer a permanent loss of capital

To suffer a permanent loss of capital, the investment has to be sold at a price that is lower than the buying price.

For simplicity, I will ignore the situation where the investment has been sold due to short-term volatility. From a value investment perspective, this is unlikely to happen.

Rather I assumed that any sale is because the price is “permanently” below the purchased price due to the following direct reasons:

- Deterioration in the intrinsic value due to changes in the fundamentals - both macro and micro.

- Issues with portfolio construction.

- Wrong assessment of intrinsic value in the first place.

- Stock market changes due to regulatory changes.

These are the main direct causes and there are other root causes for each of them.

To help identify the root causes, I have used the Ishikawa fishbone diagram to help identify the various causes and effects.

|

| Chart 2: Ways to suffer a permanent loss of capital |

The details of each of the root causes for the boxed items in the Ishikawa diagram are presented below.

Stock Market Changes

- Privatization - you are sometimes forced to sell at below your purchased price due to a privatization exercise.

- Regulatory - these relate to rules that affect the availability of the stock e.g. trading restrictions. There is a “feedback loop” here. If the business deteriorates there is a higher likelihood of some listing guidelines that may affect its liquidity.

Wrong initial intrinsic value

The assessment of intrinsic value is the heart of value investing. If this was wrongly assessed at the start, the purchase would be a mistake that would be realized much later.

- Governance. The intrinsic value is generally assessed based on the financial statements. If there are issues due to the poor quality of earnings or even creative accounting, the computed intrinsic value would be wrong.

- You could have made some analytical errors in assessing the intrinsic value. You are more likely to make errors if the company has a more complex business model.

- Your behavioral biases can skew your estimates of intrinsic value. Again, there is a high likelihood of more behavioral biases in analyzing and valuing a company with a complex business model.

Portfolio construction

- Position size. This relates to the number of stocks in the portfolio and the amount to be allocated to each stock.

- Cash management. From an individual investor perspective, the amount of cash you have affects your holding power. You should have enough to handle emergencies without being forced to sell your shares at the wrong time. The amount of cash also affects the ability to take advantage of the market but I don’t see this as critical in the context of a permanent loss of capital.

- Hedging refers to other strategies of guarding against risk eg taking a short position.

Deterioration of intrinsic value

The intrinsic value of a company could decline over time. Over the long term, the market price will decline to reflect this.

- Management could be the cause of the decline. This could be due to adopting the wrong strategy or plain incompetence.

- Financials - if the company has debt, there could be changes to the loan situation e.g. higher interest rates that affect its profitability or cash flow.

- External - this covers all the social, political, and economic changes that negatively impact the company. I would include technological changes here as well.

The above Ishikawa diagram shows the first level of cause-and-effect. You can have a second or even third level cause-and-effect diagram for the more complex cases.

For example, in the case of the External factors, you could further break it down into:

- Different economic factors e.g. interest rate, GDP growth, and inflation.

- Different social factors e.g. demographic trends, and migration patterns.

Assessing the threats

The goal of threat assessment is to evaluate the likelihood of occurrence of each of the threats and the impact.

I classify each cause in the Ishikawa diagram into one of the following 4 colored cells based on the assessment of its impact and the likelihood of it occurring as per the Chart below.

|

| Chart 3: Threat Matrix |

This is of course a qualitative assessment. But I find that it ties in neatly with the value investing approach.

For you to be able to assess and value companies, you need an in-depth understanding of the business, the competitors, and the industry. That is why staying within your area of competence is important. You tap into the same pool of knowledge to carry out the risk assessment.

It is important to be able to slot the various causes into the appropriate cells of the Threat Matrix as it helps to determine your mitigation measures.

Determining the likelihood of the cause is a judgment call based on your own investing experience.

Over my past 15 years of value investing, there have been several occasions where I have suffered a permanent loss of capital.

- Once or twice, my whole investment was wiped out because the companies went into liquidation following some fraudulent practices.

- I have sold stocks incurring some losses after waiting 10 years for the market to re-rate. I lost patience.

I have then used this experience to classify the various causes into “high” or “low” probability ones. If you don’t have sufficient experience with bad investments, I would suggest that you play safe and classify a cause as “high probability” if you are not sure.

When it comes to assessing the impact, I think along the following lines:

- If it impacts the whole portfolio, I classify it as “high impact”.

- If it affects a single stock, then I look at the consequences. If it can wipe out the whole investment, I classify it as ‘high impact”. If it only reduces a small % of the investment, I classify it as “low impact”.

For example, I would consider a deterioration in the intrinsic value due to poor management as a “high impact” one.

For my investment process, the following fall into the red cells:

- Deterioration in the intrinsic value - poor management.

- Wrong initial intrinsic value – behavioural.

- Stock market changes – privatization.

The idea of slotting the various risks into the 4 cells is because it will help you identify the risk mitigation measures.

Remember the 4 mitigation measures - Avoid, Reduce, Accept, and Transfer?

There are costs associated with each of these mitigation measures so it is important to have an idea of which cell a particular risk falls into. Generally:

- I would “Accept” the risks that fall into the green cell.

- I would “Avoid” or “Transfer” the risks that fall into the red cell.

- I would “Reduce” or “Transfer” the risks that fall into the orange cell.

- I am ambivalent about what to do when it comes to the yellow cell.

The above is a visual and qualitative approach. In theory, it is possible to assign a score to each cell so that we can have a quantitative assessment.

However, there are two challenges to such a quantitative assessment:

- How do you validate the score assigned to each of the cells?

- How do you weigh the individual threat items to derive an overall score?

The question is whether such a scoring method would provide any useful information compared to a visual assessment.

Risk mitigation

There are 2 components of risk - the chance or probability of an outcome and the impact of the outcome.

It is obvious that if there is no impact there is nothing to lose. Furthermore, if we were certain that a loss would occur, we would not have invested.

So, when there is investment risk, it is because there is uncertainty as well as a loss if the uncertain outcome occurs. This is an important risk concept for risk mitigation. In other words, to reduce risk, we can address the probability, the impact, or a combination of both.

Given the various items that can lead to a permanent loss of capital, the risk management approach is to identify various measures to handle them.

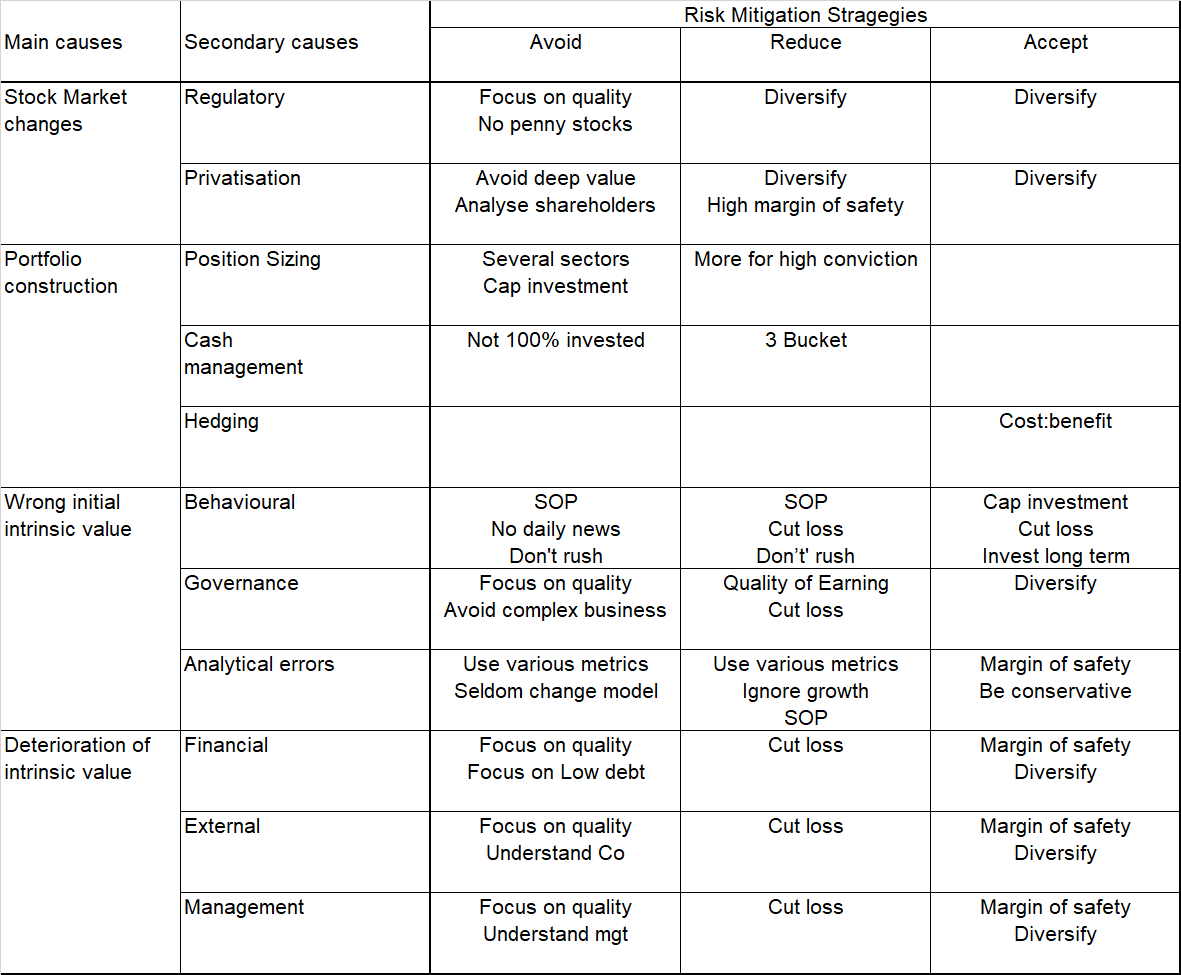

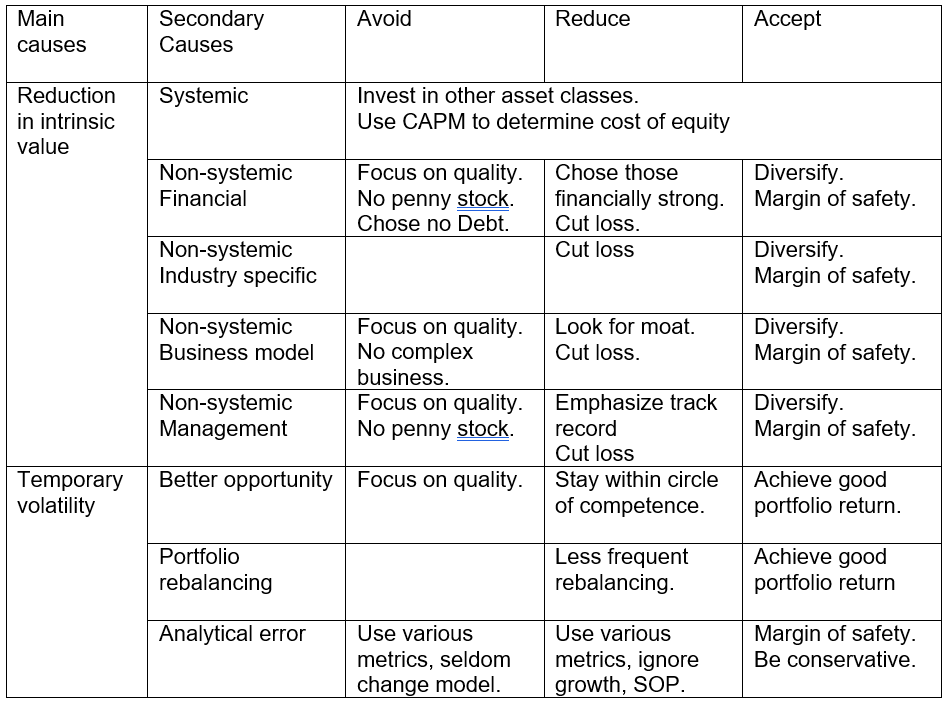

The Chart below summarizes the various measures that I have adopted categorized into:

- Avoiding the threats.

- Reducing the likelihood or impact of the threats.

- Accepting the threat.

You will notice that some measures cut across several risk mitigation categories.

At the same time, to transfer some of the risks, I have some of my net worth invested in unit trusts and properties. These have a different risk profile than those of stocks.

Furthermore, if you view the threat as a function of both the likelihood of the event and the impact of the event, then depending on the nature of the threat,

- Some of the measures focus on the likelihood.

- Some focus on the impact.

- Some cover both likelihood and impact.

|

| Chart 4: Risk Mitigation Strategies |

Most of the measures adopted a self-explanatory. But for some others, I provide a brief description (in alphabetical order) as follows:

- Analyze shareholders - privatization will also depend on whether the controlling shareholder sees any advantages in maintaining the listing status.

- Avoid deep value - deep value stocks are those that are generally trading at a deep discount to the Asset values. These are potential privatizations.

- Cap investment - this is to ensure that there is no concentration in a particular stock.

- Cost-benefit - only hedge if the benefits outweigh the cost.

- Cut loss - be prepared to sell and cut loss if you have made an error in your analysis and/or valuation.

- Don’t rush - this refers to slowly building up or exiting a position. You may likely look at a stock differently when you are invested.

- More for high conviction - this relates to investing a bigger amount for those stocks with higher conviction.

- Quality of earnings - this relates to the proportion of income attributable to the core operating activities of a business. You ignore any anomalies, accounting tricks, or one-time events.

- Several sectors - diversification is not only about investing in several companies. It is also to ensure that the stocks in the portfolio are from different sectors. The goal is to ensure that there is no concentration in any particular sector.

- SOP - have standard operating procedures.

- Understand management - evaluate management from several perspectives i.e. as an operator and as a capital allocator.

- Use various metrics - there are many metrics and techniques when it comes to valuation. Adopt a number of them to triangulate the intrinsic value.

- 3 Bucket - this refers to an asset allocation strategy where the net worth is spread into 3 asset classes i.e. liquid, safe, and risky assets.

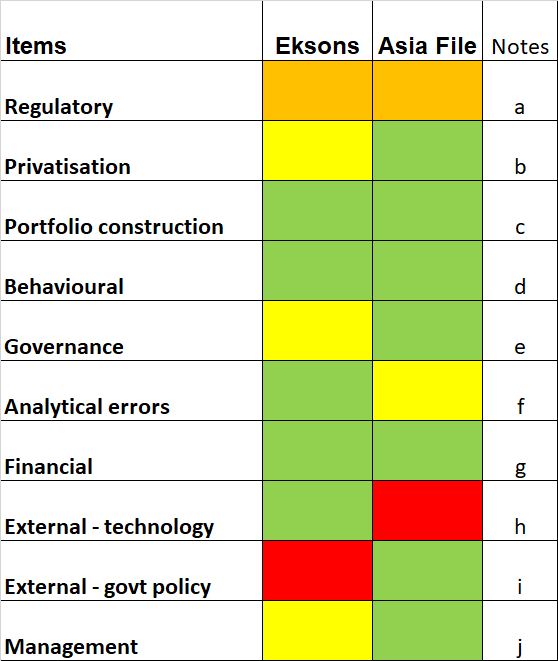

Case study - Comparative visual assessment

To be able to assess the threats there is a need to first analyze the companies. Such analyses have been carried out for 2 companies - Eksons and Asia File - whose details can be viewed on other posts in this blog.

For each company, I categorized each of the causes of permanent loss of capital (as per the Ishikawa diagram) into the relevant threat category (as per the Threat matrix).

The comparative results and rationale are tabulated below.

Based on a visual comparison, you would conclude that an investment in Asia File would have less risk compared to a similar investment in Eksons.

The above is mainly a first-level cause-and-effect assessment (although I did go down to the second level in the case of the External factors)

You can go down into a second or even third-level cause-and-effect assessment if needed.

|

| Chart 5: Comparing the risk between Eksons and Asia File through a permanent loss of capital lens |

Notes

a) Any regulatory issues affect both companies equally.

b) Because of the shareholders' profile and cash available in the company, I consider a greater likelihood of Eksons being privatized. Of course, whether you suffer a permanent loss of capital would depend on your purchased price.

c) Since both stocks are in the same portfolio, they share the same risk profile and hence I have not attempted a finer breakdown.

d) I use the same analytical process for both so they share the same assessment. My margin of safety minimizes the impact of any error here.

e) I relied on the Q Rating to assess Eksons to be riskier. My margin of safety minimizes the impact of any error.

f) Eksons has a simpler business model and hence fewer analytical and valuation issues.

g) Both companies are financially strong.

h) Asia File is more likely to face digital disruption.

i) Eksons is facing log supply issues resulting from the government logging policies. Note: this comparison was done before Eksons ceased the plywood operations that used logs as its raw materials.

j) Asia File management has a stronger track record.

What to do with the results

Although this is a simple visual assessment, I have used the results in the following manner:

- Position sizing. The concept behind the Kelly Formula is to invest more in those with the greatest payoff and the best probability of success. I translate this to mean that I invest more in Asia File compared to Eksons. I believe that this is in line with the idea that you invest more in those with a higher conviction.

- The margin of safety. This margin is to protect you against bad luck and other errors made in the investment process. I would require a smaller margin of safety for Asia File compared to Eksons.

Pros and Cons of the Methodology

The goal of the assessment is to have a standard way of comparing the risk between several companies.

A visual assessment serves this purpose. Unfortunately, it is not very meaningful if you want to assess the risk of just one company.

I see the following as the Pros and Cons of this approach.

Pros

- Simple visual assessment.

- A consistent basis to compare.

- Relates to the reasons for permanent loss of capital ie risk.

Cons

- Requires detailed analysis of each company.

- May not be practical to compare many companies together.

- Different parties may come to a different assessment.

- Dependent on identifying the correct cause-and-effect.

Volatility

In this section, let us look at why volatility can be considered a risk even for a value investor. I will then use my risk mitigation framework to bring it into the risk mitigation process.

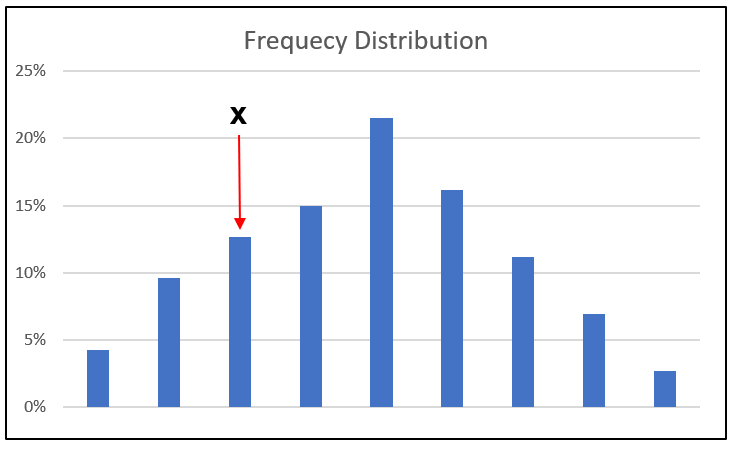

Imagine that you invest in a stock that costs x. The outcome is uncertain so the exit price could be less or even more than x. If it is less than x, there is a loss.

Suppose that we have historical data showing the distribution of prices around some expected mean. Refer to Chart 6.

|

| Chart 6: Distribution of Prices about the Mean |

Statistically, the distribution has a mean. We can measure the distribution of the data around the mean with the standard deviation or variance (square of the standard deviation).

Let us look at this in the context of x. Based on this distribution we could calculate the frequency of the price being less than x. We can then compare this with all the frequencies and determine the probability of the price being less than x. This can be interpreted as the risk of the stock. You can see that if the standard deviation is bigger, the risk of the price being less than x could be bigger and vice versa.

You can see why the standard deviation or variance can be used to measure risk. A stock with a bigger standard deviation would be considered riskier than one with a smaller standard deviation. Conventionally many use the term “volatility” to describe the variance.

The argument from the permanent loss of capital school is that volatility is only crystalized into a permanent loss of capital if you sell when the price is less than x. If you view volatility as temporary and do not sell the stock, you have not suffered any loss. That is why the permanent loss of capital school does not believe that volatility is a good measure of risk.

I would argue that there are times when you crystallize the loss even though you know that the price volatility is temporary. For example:

- You sell due to some portfolio rebalancing rule.

- You have made a mistake in estimating the intrinsic value.

- You found a better investment opportunity.

Because of these, it is better to not rule out volatility as a risk even though I follow the permanent loss of capital school.

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT)

MPT is based on the view that variance represents risk.

When you create a stock portfolio there are two parameters at your disposal.

- You can select the stocks to be included.

- You can also determine the proportion of a stock relative to all the stocks in the portfolio. This is commonly referred to as the weight of the stock in the portfolio. This can be computed based on the cost of the investment or the value of the stocks.

Let us consider the case where you have selected the stocks and are now looking at various portfolio options based on changing the weights. You are looking at the impact on the portfolio return and variance.

- The return of the portfolio is the weighted average return of the individual stocks in the portfolio.

- The variance of the portfolio is not the weighted average variance of the stocks in the portfolio. The portfolio variance is dependent on the variances of the various stocks in the portfolio amended by the covariances. If you have uncorrelated or even lowly correlated stocks, you can have a portfolio variance that is less than the lowest stock variance.

|

You can see the benefits of diversification. The portfolio variance can be reduced with uncorrelated stocks. If you consider variance as a risk then the risk is reduced with the portfolio.

MPT provides a numerical basis for the adage that you should not put all your eggs in one basket.

I have a stock portfolio as part of my risk mitigation plan. While I do not use MPT to construct my stock portfolio, I follow the principle that it should have uncorrelated stocks.

Furthermore, I target about 30 stocks. This is because studies have shown that the benefits of diversification become marginal after this number. These studies generally use volatility as the measure of risk with Chart 7 as a typical one.

You can understand why there would be inconsistencies if I did not consider volatility as a risk.

|

| Chart 7: Risk vs. Number of Stocks in a Portfolio |

The permanent loss of capital school does not have a quantifiable basis for constructing a stock portfolio. If you do not consider volatility as a risk, can you adopt the MPT approach when constructing a portfolio? You can see the dilemma.

The mental gymnastics I used to get out of this dilemma was as follows:

- While the variance can be considered a measure of risk, covariance is not exactly volatility. But because it can be used to reduce portfolio volatility, people sometimes confuse it with the measure of volatility.

- In other words, although I do not consider volatility a risk, this is okay as MPT focuses on covariance rather than variance.

I now think that it is better to consider volatility as another component of risk rather than disregard it completely. Then you do not need some mental gymnastics to rationalize using MPT.

Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)

I used CAPM to determine the cost of equity. This is then used to determine the WACC which is the discount rate (the expected return) used when estimating the intrinsic value of the firm.

According to Investopedia, CAPM is a finance model that establishes a linear relationship between the required return on investment and risk. And of course, the risk under CAPM refers to volatility.

You can see the anomaly. As a person following the permanent loss of capital school, I am relying on a volatility-based theory to determine the cost of equity. I used to justify this by arguing that there was no better theory.

I now believe that it is wrong to treat volatility and permanent loss of capital as mutually exclusive. My view now is that they both represent different dimensions of risk.

According to CAPM, the expected return of a stock depends on the stock Beta, the risk-free rate, and the equity risk premium. This is represented by the following equation.

Er = Rf + Beta X (Rm – Rf)

Where:

Er = expected return

Rf = risk-free rate

Rm = market return

Rm – Rf = equity risk premium

The Beta of a stock is a measure of how much risk the stock will add to a market portfolio. If a stock is riskier than the market, it will have a Beta greater than one. If a stock has a Beta of less than one, the formula assumes it will reduce the risk of a portfolio.

The key concept here is that risks are separated into systemic and non-systemic risks.

- Systemic risks refer to the risks inherent to the entire market or market segment. It is also known as “undiversifiable risks,” or “market risks,” as they affect the overall market and not just a particular stock.

- Non-systemic risks refer to risks that are not shared with a wider market or industry. These are risks often specific to an individual company due to its management or business model. Unlike systemic risks, non-systemic risks can be reduced by diversifying one's investments.

Systemic risk is impossible to avoid. It cannot be mitigated by diversification. To account for the systemic risk, you require the stock to deliver a return that is equal to or higher than those determined by the CAPM.

There are 2 takeaways from CAPM when formulating your risk mitigation plan.

- If you hold a concentrated portfolio, you face more of the non-systemic risks.

- An investor can identify the systemic risk of a particular stock by looking at its Beta. You aim for a higher return when investing in a particular stock relative to that calculated with CAPM.

It is obvious that in addition to seeking a higher expected return, you should also adopt measures that address systemic risks. For example, you could invest in other asset classes.

Beta

Beta is calculated by dividing the product of the covariance of the stock's returns and the market's returns by the variance of the market's returns over a specified period. It can be represented by the following equation:

Beta = Covariance (Re, Rm) / Variance Rm

Where:

Re = the return on an individual stock.

Rm = the return on the market.

In statistical terms, Beta represents the slope of the line through a regression of data points. In finance, each of these data points represents an individual stock's returns against those of the market.

You can see from the above equation that Beta relates to volatility. Beta is a measure of the volatility of a stock compared to the market. Ultimately, you are using Beta to try to gauge how much risk a stock is adding to a portfolio relative to the market risk.

- If a stock has a Beta of 1.0, it indicates that its price activity is strongly correlated with the market. A stock with a Beta of 1.0 has systemic risk. In the Bursa Malaysia context, companies like Hap Seng Consolidated and TH Plantations have levered Beta of around 1.0

- A Beta value that is less than 1.0 means that the stock is theoretically less volatile than the market. Including this stock in a portfolio makes it less risky than the same portfolio without the stock. Examples of Bursa Malaysia companies with a levered Beta significantly less than 1.0 are Suria Capital and Ajinomoto.

- A Beta that is greater than 1.0 indicates that the security's price is theoretically more volatile than the market. Examples of Bursa Malaysia companies with a levered Beta of greater than 1.2 are Notion and Heitech Padu.

|

An integrated risk management framework

I had earlier presented a risk management framework comprising several elements.

- The Ishikawa of Fishbone diagram to identify the root causes of a permanent loss of capital.

- A Threat Matrix to assess the likelihood and impact of each of the risks.

- A Risk Mitigation Matrix to ensure that we have measures to mitigate each root cause.

In those articles, I used the framework to analyze risk only as a permanent loss of capital. I will now use the same framework but consider both volatility and permanent loss of capital.

Identifying the root causes

In the earlier part of the article, I identified 4 main causes that can lead to a permanent loss of capital:

- Deterioration of intrinsic value.

- Portfolio construction.

- Wrong initial intrinsic value.

- Stock market changes.

Refer to Chart 2 reproduced below.

|

| Chart 2: Causes of Permanent Loss of Capital (Reproduced) |

If I now include volatility as another component of risk, I would retain the latter 3 items. However, I would replace the “deterioration in intrinsic value” with 2 other main causes as shown in Chart 8:

- Reduction in intrinsic value due to either systemic or non-systemic risks. You can see that I have sub-causes for the systemic and non-systemic components.

- Temporary volatility that was crystalized to invest in a better opportunity. It can also be for portfolio rebalancing reasons or because of analytical errors.

|

| Chart 8: Update Fishbone Diagram incorporating Volatility |

I have also identified 4 sub-causes each for the systemic and non-systemic components. In other words, to address the systemic and or the non-systemic risks, you address the respective sub-causes.

As for the sub-causes for the Stock market changes, Wrong initial intrinsic value, and Portfolio construction, refer to the earlier section.

You can see that by considering volatility as a risk, there is a more comprehensive picture. The segregation of risks into systemic and non-systemic ones shows that you need to address both if you are not well-diversified. At the same time, you cannot rule out losses due to temporary volatility.

Threat matrix and risk mitigation measures

Once you have identified the various causes of risks, you can then assess the impact using the Threat matrix. Thereafter you establish the respective risk mitigation measures for each of the causes.

In this section, I will jump straight to the risk mitigation measures for the systemic, non-systemic, and temporary volatility components. If you want detail on the other components, refer to Chart 4.

Chart 9 summarizes the risk mitigation measures for the systemic, non-systemic, and temporary volatility components. Note the following:

- There is nothing much you can do about the systemic risks. You cannot avoid or reduce them. I have identified 2 measures to live with such risks. The first is to invest in other asset classes such as properties and bonds. The second is to follow the volatility school of aiming for a higher return for taking on the risk. This is achieved by using CAPM to determine the cost of equity.

- Many of the measures listed in Chart 9 are also the ones that I have established under the previous framework.

- There are some cells in Chart 9 where I could not identify a suitable risk mitigation measure. This is not so bad as there are other measures for that particular cause.

|

| Chart 9: My Risk Mitigation Measures Note: For the other measures, refer to Chart 4 |

Behavioral dimension

When you look at the measures in Chart 9, you can see that there are many behavioral aspects. You should not be surprised as there are 3 decisions to consider when investing:

- What to buy?

- How much to buy?

- When to buy?

From a value investment perspective, the buy and sell decisions are based on the market price relative to the intrinsic value.

But to derive the intrinsic value, you have to understand the business and make assumptions about its prospects, etc. These affect your valuation. Any biases you have then affect your valuation and hence your buy and sell decision.

When it comes to how much to buy, this is generally dependent on the amount you allocate to the total portfolio and the number of stocks you want to hold. At the same time, unless you allocate an equal amount to all the stocks, the likelihood is that you will allocate a bigger sum to the stocks with the highest conviction.

Again, you can see how behavioral biases affect this decision.

Can you mitigate these? There are several things that I do:

- Have a standard procedure.

- Don't listen to the news.

- Don't rush into things.

- Take a long-term view.

The reality is that behavioral biases are one of the risk elements in investing. Investing success is dependent on behavior rather than intelligence.

Investment risk tolerance

From a behavioral angle, your risk tolerance plays a role in your risk mitigation measures.

I like to think of risk tolerance as the % of your savings you can afford to lose without fretting about it.

- A 100% risk-tolerant person thinks nothing of losing 100% - these are the addicted gamblers.

- Then there is the 0% risk-tolerant person who gets upset even losing 1%.

When it comes to investing, there are 100% risk-tolerant persons - just imagine those who blindly trade/invest.

However, I don’t think there is any 0% tolerant person. To invest you need some risk tolerance.

Having said that, being some 10% to 20% risk-tolerant doesn’t mean that you simply trade/invest. In other words, being risk-tolerant does not mean that you sit back and accept the risk of losing money.

There are a host of measures to adopt so that while being risk-tolerant, you end up with a minimal permanent loss of capital.

I have seen several “questionnaires” over the years that try to establish your risk profile for investment purposes.

At the end of the day, if you are knowledgeable about investments, you don't need a questionnaire to tell you your risk tolerance.

Warren Buffett has the saying that risks come from not knowing what you are doing. I think this aptly describes my point.

Pulling it all together

Risk management involves identifying the threats, assessing, and then mitigating them. You consider both the likelihood of the event happening and its impact.

I have presented a risk management framework comprising several elements.

- The Ishikawa diagram to identify the root causes of a permanent loss of capital.

- A Threat Matrix to assess the likelihood and impact of each of the risks.

- A Risk Mitigation Matrix to ensure that we have measures to mitigate each root cause.

The framework shows how to mitigate risk from a permanent loss of capital perspective. I have also shown how this framework can be used to bring volatility into the risk mitigation process.

As a value investor, I do not follow the volatility school when it comes to risk. However, I do use some of the volatility concepts in my valuation. As such it does not make sense to ignore volatility.

But there is no need for this if you view volatility as another risk component. By considering volatility and permanent loss of capital as different components of risks, you can have a more comprehensive picture. At the same time, MPT and CAPM concepts can then be part of your fundamental analysis.

The permanent loss of capital school does not have a quantitative measure of risk while the volatility school has managed to do this via the variance. However, variance is not a precise measure of risk. But in certain circumstances, an imprecise measure is better than no measure.

I hope that I have made a case that even if you follow the permanent loss of capital school, there is a basis for considering volatility.

My risk mitigation measures

What you adopt will depend on your situation. My measures include the following:

1) Adopt a conservative approach in the valuation. Use conservative estimates for the various valuation parameters. For example, if there are growing trends for the profits and/or cash flows, any valuation that assumes zero growth will be conservative.

2) Have different levels of the margin of safety depending on the nature of the investment. For example, have a larger safety margin for companies going through a turnaround compared to one with a "consistent" track record. I also choose companies with some dividend track record as I consider dividend payment as some form of margin of safety.

3) Focus on quality stocks and those with a long operating history to guard against fraud and the business environment. I have incorporated several academic quality and risk indicators in my analysis. Examples are the Beneish M Score, the Piostroski F Score, and the Altzman Z Score.

4) Diversify. I adopt a 2-tiered diversification plan. Firstly, I invest in several asset classes with equity as only one of them. Secondly, I hold a portfolio of about 30 to 40 companies. These are from different sectors and market capitalization categories of investments.

5) Understand the company. Get a good picture of how it got to its present position. Understanding its business model and strategies helps me get a handle on its fundamental and macroeconomic risks.

6) Invest in the long-term. This helps to mitigate any short-term economic upheavals.

7) Be prepared to cut loss if the investment thesis is no longer valid. I have done this several times. While there are some initial losses, I can more than makeup for the losses by investing the money in other companies with better prospects.

8) Invest more in those where you have more confidence. This is related to the position sizing strategy.

9) Incorporate Beta into the valuation. When I first started, I used one discount rate in my valuation. To account for the risks, I now use the Capital Asset Pricing model to determine the discount rate.

10) At the end of the day, the best risk mitigation strategy is to look at the investment from the downside protection perspective. Let the upside take care of itself. Don’t think of the returns that can be made. Rather think of how to prevent losses.

End

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

How to be an Authoritative Source, Share This Post

|

Disclaimer & Disclosure

I am not an investment adviser, security analyst, or stockbroker. The contents are meant for educational purposes and should not be taken as any recommendation to purchase or dispose of shares in the featured companies. Investments or strategies mentioned on this website may not be suitable for you and you should have your own independent decision regarding them.

The opinions expressed here are based on information I consider reliable but I do not warrant its completeness or accuracy and should not be relied on as such.

I may have equity interests in some of the companies featured.

This blog is reader-supported. When you buy through links in the post, the blog will earn a small commission. The payment comes from the retailer and not from you.

Comments

Post a Comment